I take a crack at answering one of the perennial questions of Spider-History.

A quick disclaimer. I’ve fallen a bit behind on current continuity so it’s possible there is new information to add to the below. If so let me know in the comments.

J. Jonah Jameson is one of the most important characters in Spider-Man’s mythology. His debut goes all the way back to Amazing Spider-Man #1.

For most of his history he waged nigh unending smear campaign against the web-slinger. And yet, even though his opposition to Spider-Man has at times been extreme and even downright obsessive, the precise reason why he has a problem with Spider-Man has been debated and contested for decades. Let’s see if we can resolve that shall we?

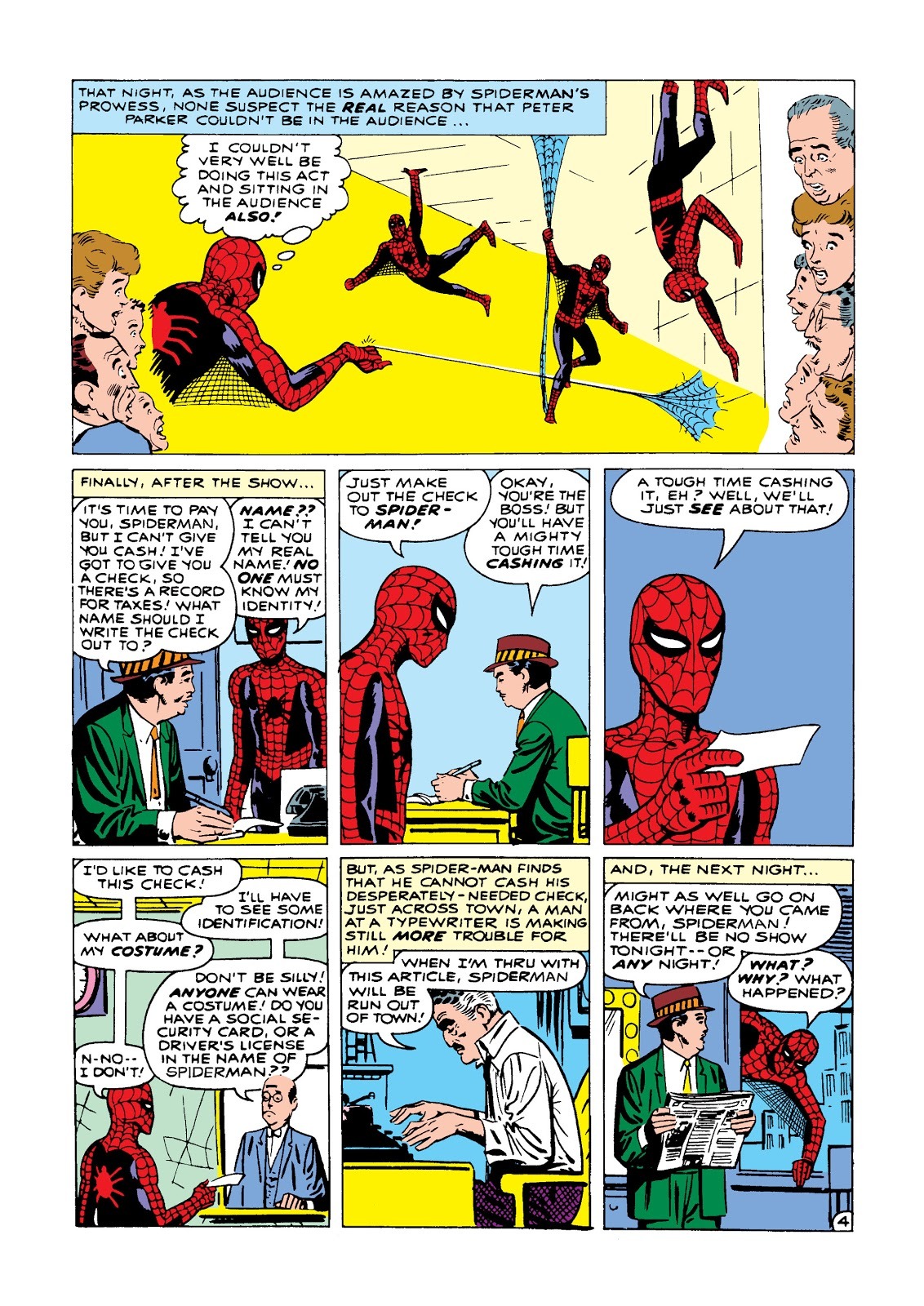

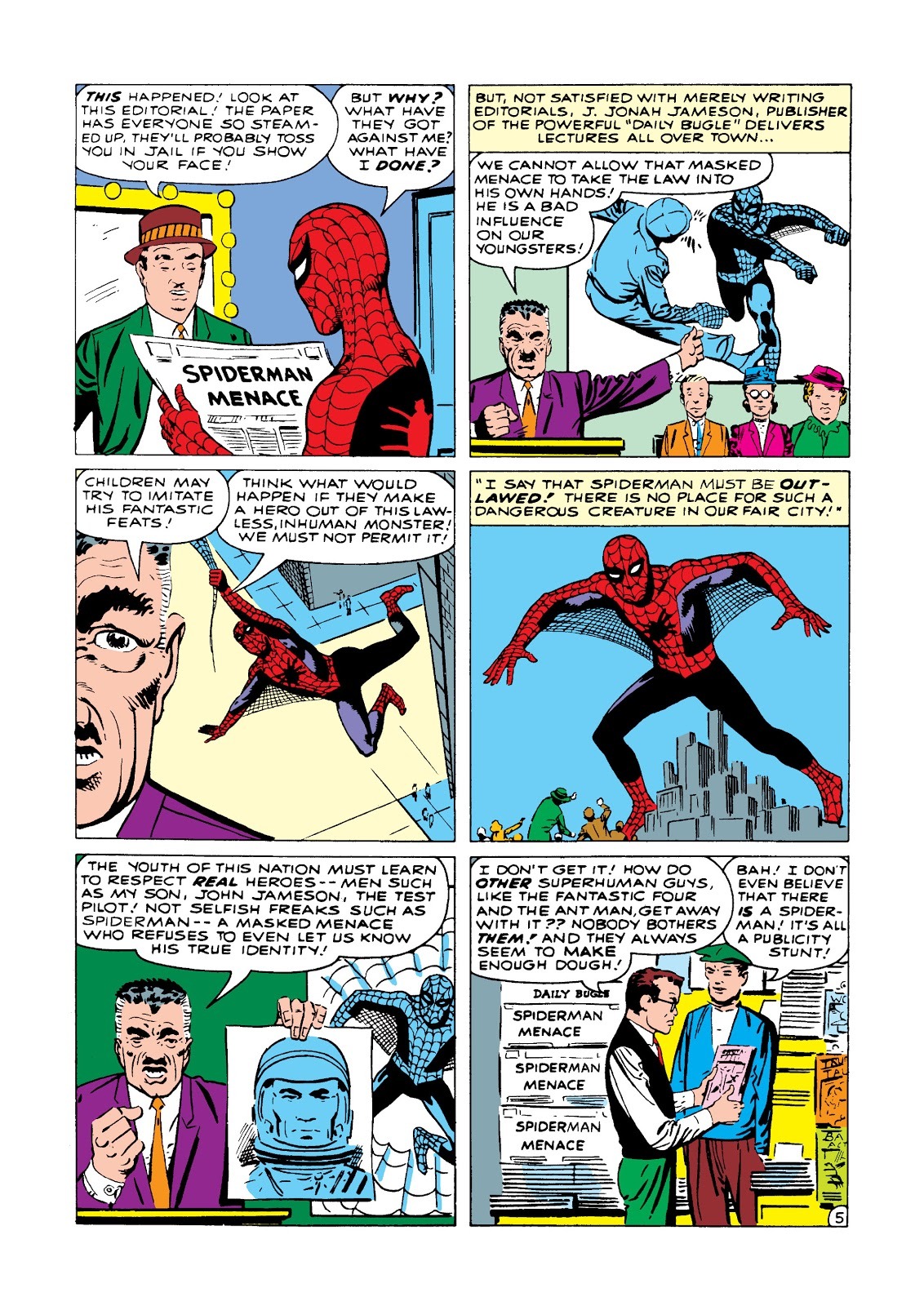

Back in ASM #1, J. Jonah Jameson kicked off his campaign against Spider-Man not merely in printed newspapers (as he’s mainly remembered for doing today) but also lecture tours and potentially TV broadcasts.

It is interesting that Jonah took to public speaking in his crusade against Spider-Man. Stan Lee claimed in the past that he always thought of himself as Jonah and for a time Stan went on speaking tours, delivering lectures primarily to college campuses. That was a few years off from ASM #1 but is worth noting all the same.

More poignantly though, the idea of an older man writing articles and delivering lectures condemning a superhero (and being taken seriously) strongly evokes Frederic Wertham, who’s book ‘Seduction of the Innocent’ and public statements condemned the harmful effects of comic books. It was partially Wertham’s actions that led to the creation of the Comic Code Authority which heavily censored and sanitized comic books and were heavily influential at the time of Spider-Man’s earliest publications. The comparison to Wertham to my knowledge was never outright stated by Stan Lee or Steve Ditko, but is an observation made by iconic Spider-Man writer Gerry Conway in the 2006 essay book ‘Webslinger: Unauthorized Essays On Your Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man ’.

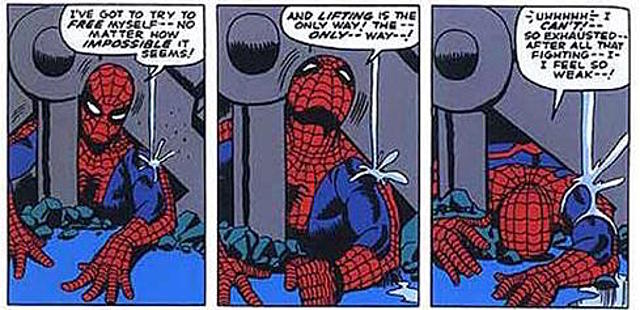

However, Steve Ditko might also have seen Jonah as a metaphor for the people/aspects of his own life that treated him unfairly; not dissimilar to Peter Parker’s lot in life. After all, the iconic rubble scene in the ‘Master Planner Trilogy’ was intended to be symbolic of Ditko himself overcoming the burdens and obstacles in his own life. Jonah was certainly one of the biggest obstacles for Spider-Man himself.

In his intriguing article ‘Spider-Man Shrugged: The Lack of Randian Heroes in The Amazing Spider-Man’ author Desmond White writes about Objectivism and Spider-Man. Objectivism is a philosophy primarily attributed to Ayn Rand, and it is well documented that Ditko was a follower of both.

White’s article says this about Jameson and Objectivism:

As the article observes, Jameson may well have been based upon Stan from Ditko’s point of view. Just not in the good natured way Stan might have believed.

Rand’s philosophy additionally, to my understanding, takes a pretty black and white assessment of human morality. One of the hallmarks of Ditko’s ‘Mr. A’ series is the titular character’s black and white calling card, representing how there is only black and white, with no room for morally grey people.

So Jameson was meant more as a commentary and an obstacle than a true blue character in his own right, at least when he debuted. No matter what he was intended to be, Jameson making Spider-Man’s life difficult was the primary consideration.

And it is perhaps because of this (as well as the push and pull between Lee and Ditko’s artistic intents for the Spider-Man series) that Jameson became exaggerated overtime and his motivations somewhat questionable. It didn’t help that Stan at the very least clearly found comic relief in the character, rendering him something of a joke. His default reaction to any given situation was to assign blame to Spider-Man regardless of almost any circumstance.

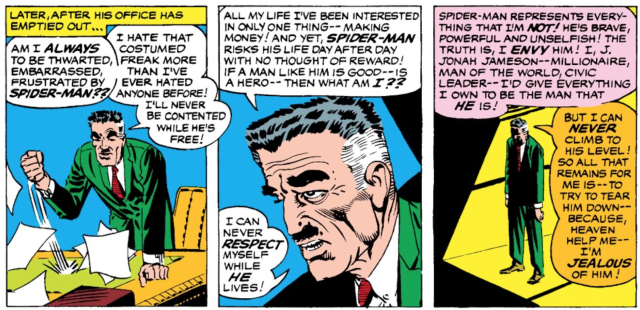

Nevertheless, in Amazing Spider-Man #10 the duo provide a new motivation for Jameson’s hatred of Spider-Man. In short, Jonah was jealous of Spider-Man. In his eyes, the fact that he’s pursued money his whole life whilst Spidey risks his life selflessly made Jonah incapable of respecting himself. Unable to rise to Spidey’s level Jonah instead dedicates himself to bringing him down to his own level.

The explanation obviously contradicts Jonah’s apparent desire for genuine public well being in ASM #1. Which isn’t damning of the moment at all as it is a dramatic reveal that helped flesh out Jonah’s truly irrational behaviour. And of course previous issues also alluded to Jonah being money grubbing and penny pinching, implying his vendetta against Spider-Man was at least as much about making money off of sensationalism as it was about any kind of genuine public concern. Jonah’s lack of sincerity might even have been hinted at in ASM #1 when he compared Spider-Man negatively to his son John Jameson the astronaut.

This explanation for Jonah has been contested by some fans since they see it as too flimsy to justify the absolute extremes Jonah goes to in his war against Spider-Man. Equally fans have questioned this explanation as it’d means Jonah would place his own inadequacies before the risks and ramifications of his vendetta. After all, Jonah has literally created super villains and funded dangerous robots to end Spider-Man.

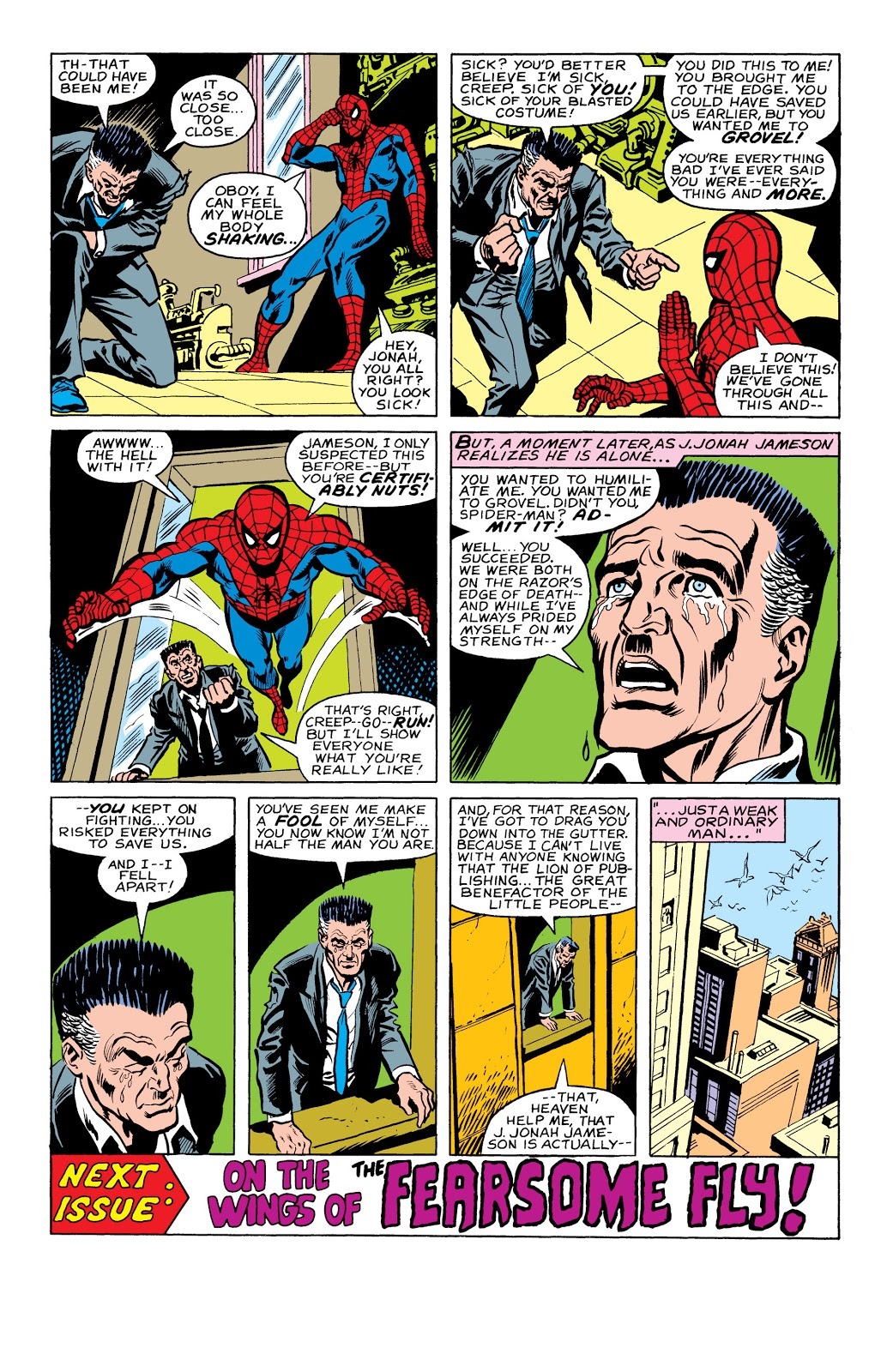

However other fans see it as a perfectly plausible motive for Jonah. One such fan was comic book legend Marv Wolfman who in ASM #192 built upon Jonah’s given motive to great effect.

Personally I can see the logic underpinning this motive, but I also find it flawed.

By the time of ASM #1 Spider-Man had not been particularly active as a superhero in order to justify Jonah’s jealously (at least not to the degree we see). Certain flashback stories present Spider-Man as being more active as a crime fighter in between his origin and ASM #1. Even then there would be too few incidents of heroic activity on Spider-Man’s part for Jonah to be so jealous of him that he’d launch such a deep seated and irrational smear campaign.

It also doesn’t quite add up when you consider other heroes (such as the Fantastic Four) were also active at the time. These heroes had also dedicated their lives to not just saving the world but scientific and exploratory endeavours which benefitted mankind. Like Spidey (from Jonah’s POV) they too did it with no thought of real reward. Shouldn’t they have equally belittled Jonah too? Shouldn’t he be trying to drive them out of town as well?

Granted, I feel we should suspend our disbelief when it comes to the shared universe nature of superhero comics and only take into account the events and characters relevant to the series under discussion. After all every Iron Man or Captain America story could in theory be solved through a simple phone call to Avengers or SHIELD for backup.* Additionally later stories published throughout the Marvel universe depict Jonah as having problems with other superheroes rather than just Spider-Man.**

Over all this explanation can work and be accepted but it wasn’t the best thing that Lee or Ditko could’ve dreamed up, even if it does give Jonah a lot of interesting characterisation and flaws.

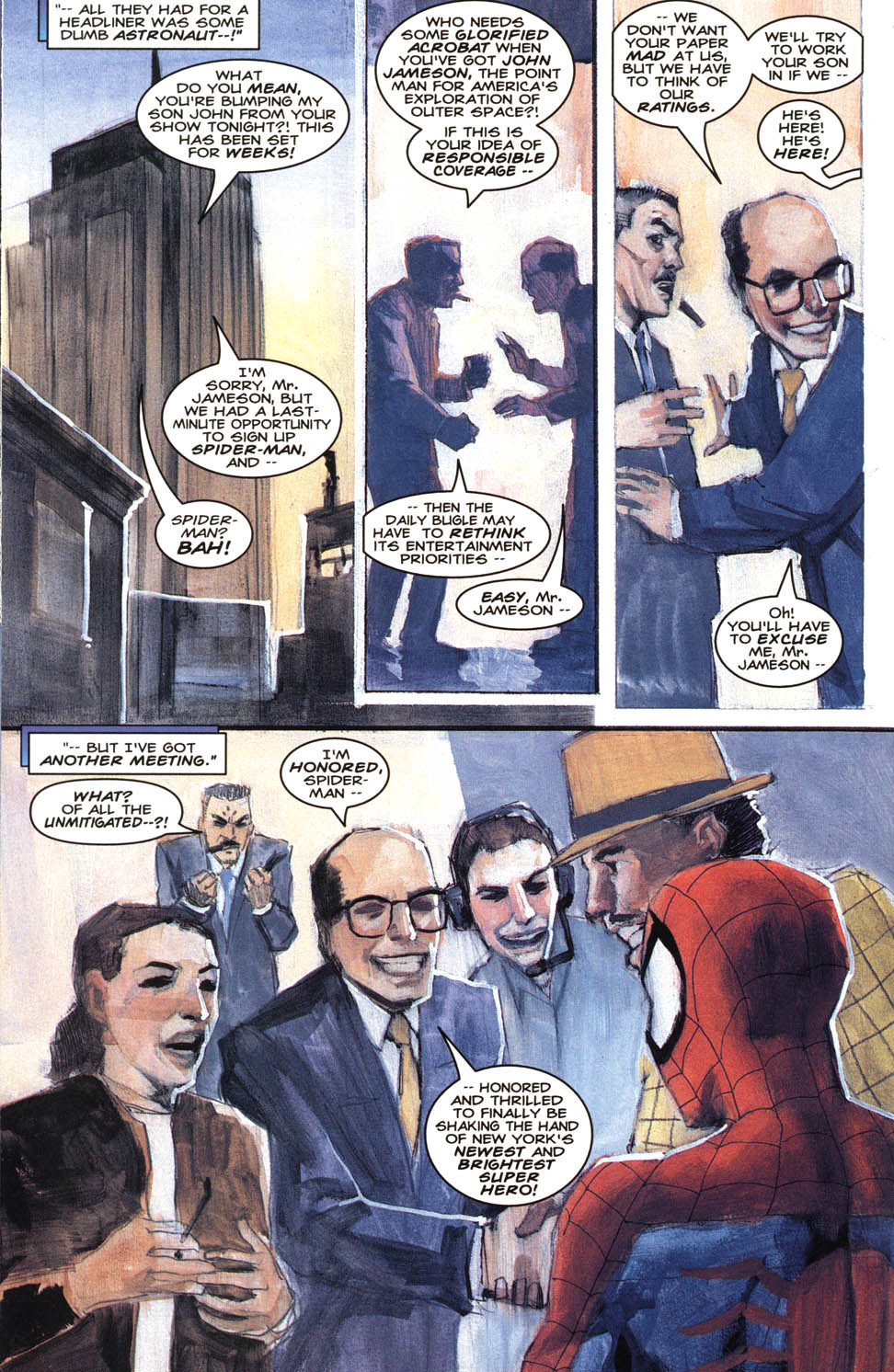

This motivation was seemingly contradicted however in Amazing Fantasy #18 by writer Kurt Busiek. Busiek in the mid-1990s produced flashback stories which were intended to fit into continuity of Spider-Man’s earliest days. Amazing Fantasy #16-18 were among these and in the final issue he presented a different explanation for Jonah’s animosity. In the issue Jonah was angry about Spider-Man getting top billing over his son, as well as his devil may care attitude.

In this issue Jonah was still somewhat jealous and concerned for the public wellbeing. But the jealousy was on behalf of his son not himself. In many ways this motivation accurately sets up what we see in ASM #1 but doesn’t explain Jonah’s deeper problems with Spider-Man that drive him to truly irrational ends.

In X-Factor #216 another legendary Spider-Man writer, Peter David, had Spider-Man guest star. He used the opportunity to provide another explanation for Jonah’s hatred of Spider-Man.

This explanation hinged upon the timing of Spidey’s arrival. He was a masked man showing up hot on the heels of the publically known Fantastic Four. This naturally raised questions about what he had to hide and how accountable he could be if he operated with anonymity.

I don’t like the criticism of Spider-Man here as it is very unwarranted. But it is interesting that PAD goes entirely against Lee/Ditko by presenting Jonah’s motive as actually being misguidedly altruistic. It builds upon Jonah as a genuine journalist and actually incorporates the Fantastic Four in a way that makes sense.

At the same time it plays upon the themes of masks and responsibility, common elements of the Spider-Man franchise.

The idea that Spider-Man’s anonymity was Jonah’s primary bone of contention is an idea that was utilized around 16 years earlier in the ‘Sting of the Scorpion’ episode of Spider-Man the Animated Series. In that episode, Jonah’s vendetta against Spider-Man stems from his wife being killed by a masked criminal. The criminal was trying to kill Jonah after he refused to back off an organized crime story. He was presumably never caught and so Jonah vowed to keep the city safe from people who hid behind masks and believed themselves to be above the law.

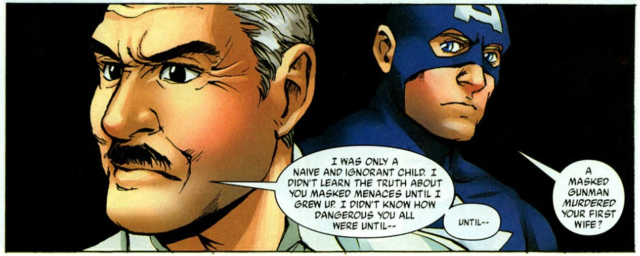

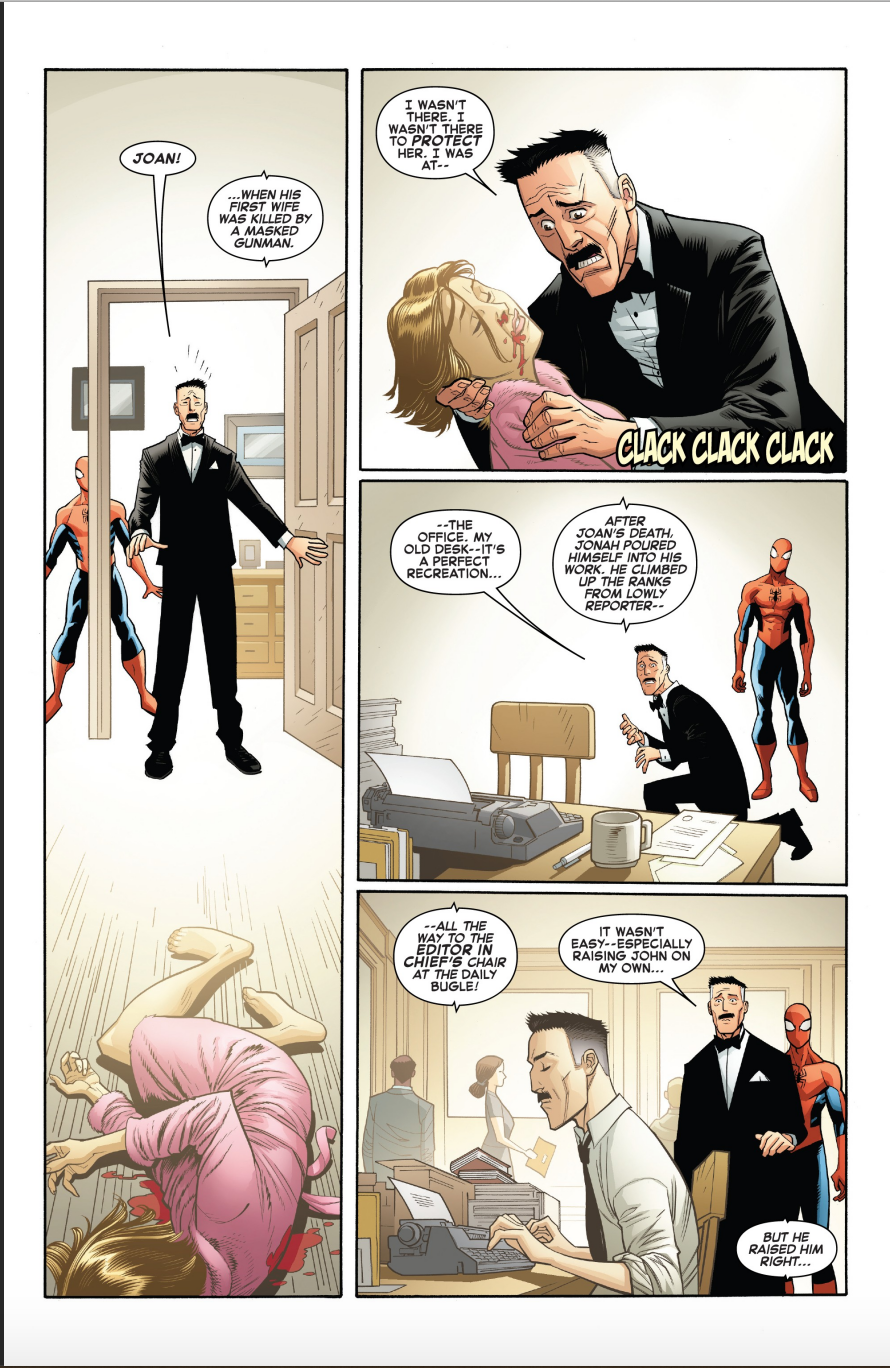

This idea was somewhat incorporated into 616 canon, specifically by the Marvel Holiday Special 2004. The story is essentially ‘A Christmas Carol’ with Jonah in the place of Scrooge and various Marvel characters as the ghosts; specifically Captain America represents the ghost of Christmas past. It is through him we first learn that Jonah’s wife Joan was murdered by a masked man.

This was an idea even more firmly brought into canon by ASM v5 #12; a.k.a. ASM #813.

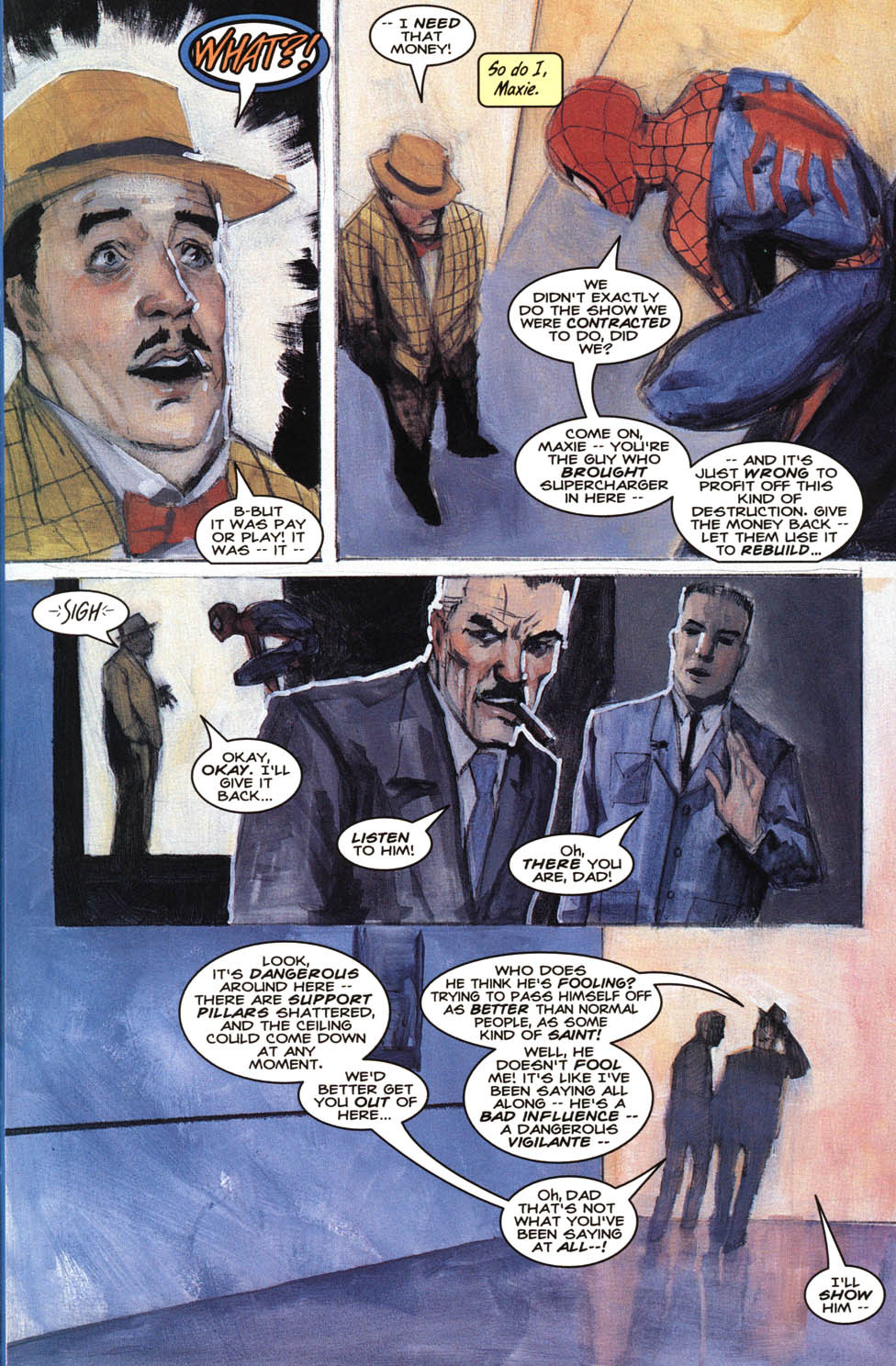

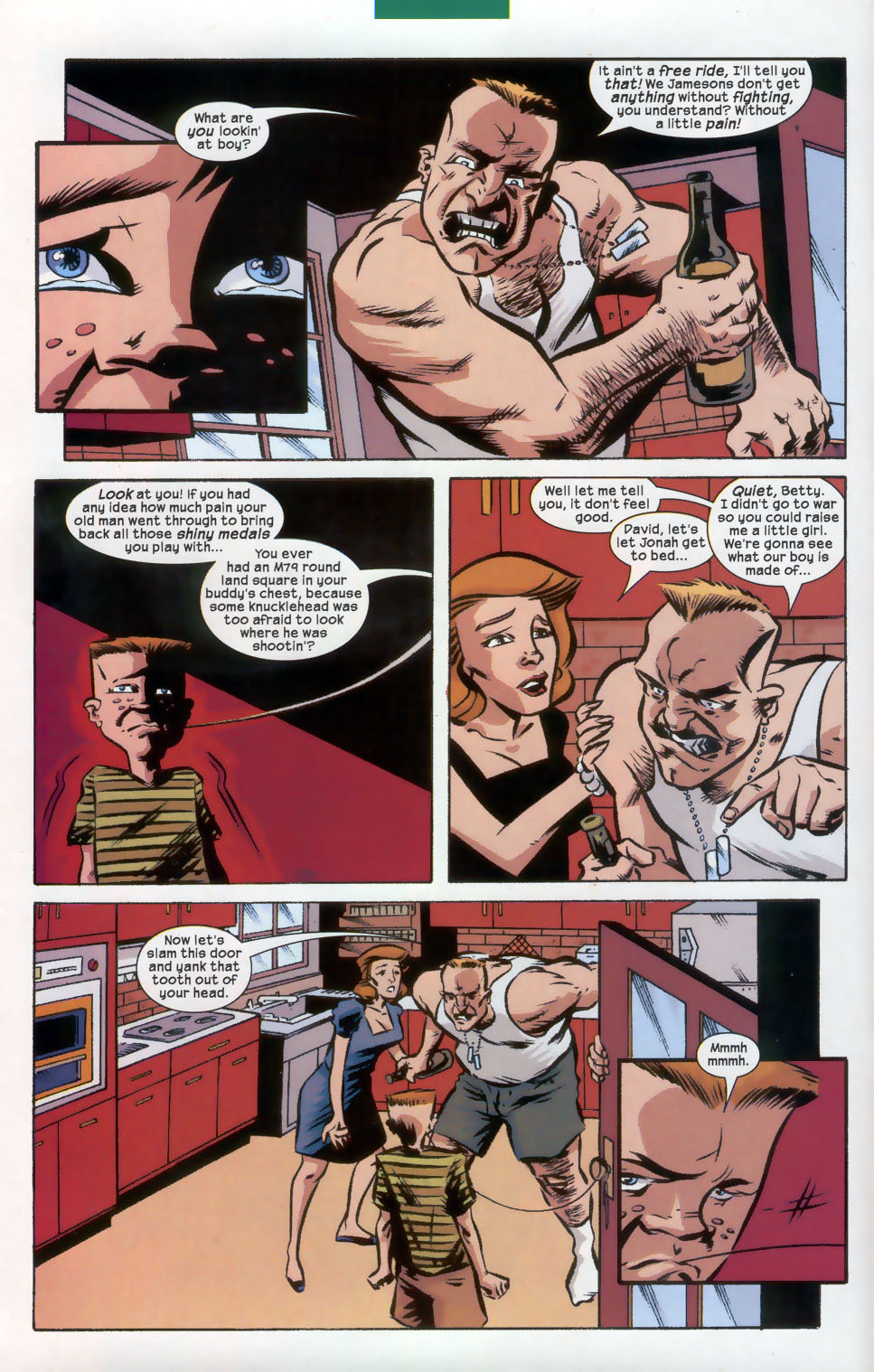

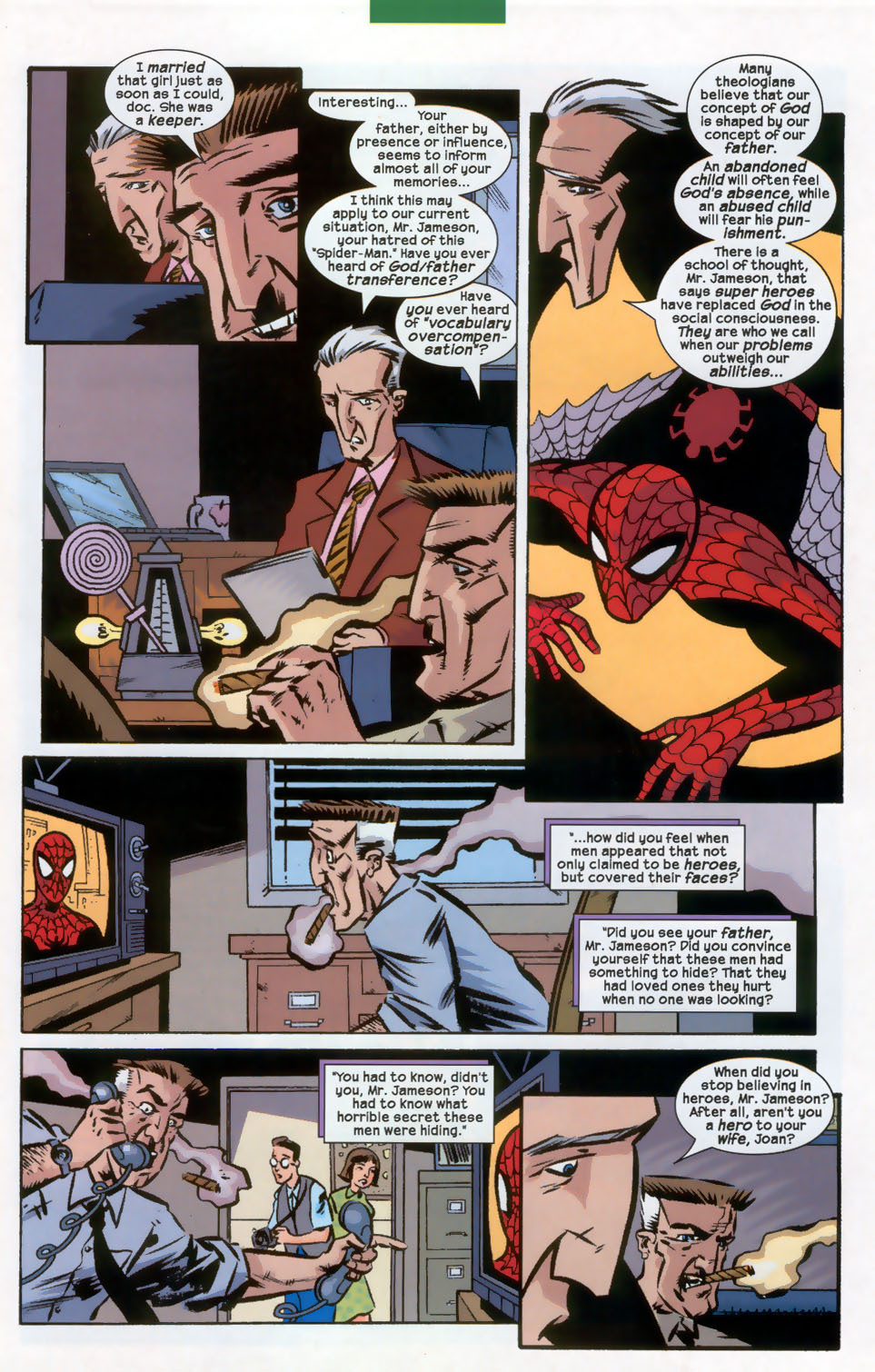

However, a far more elaborate explanation for Jonah’s hatred of Spider-Man (and for his general demeanour) was provided by Spider-Man’s Tangled Web #20; written by Zeb Wells. The story is effectively as an origin story for Jonah.

This story also disregarded the jealousy angle of Lee and Ditko. Instead it touched upon the anonymity idea that prior mentioned tales played with; albeit in a very different way.

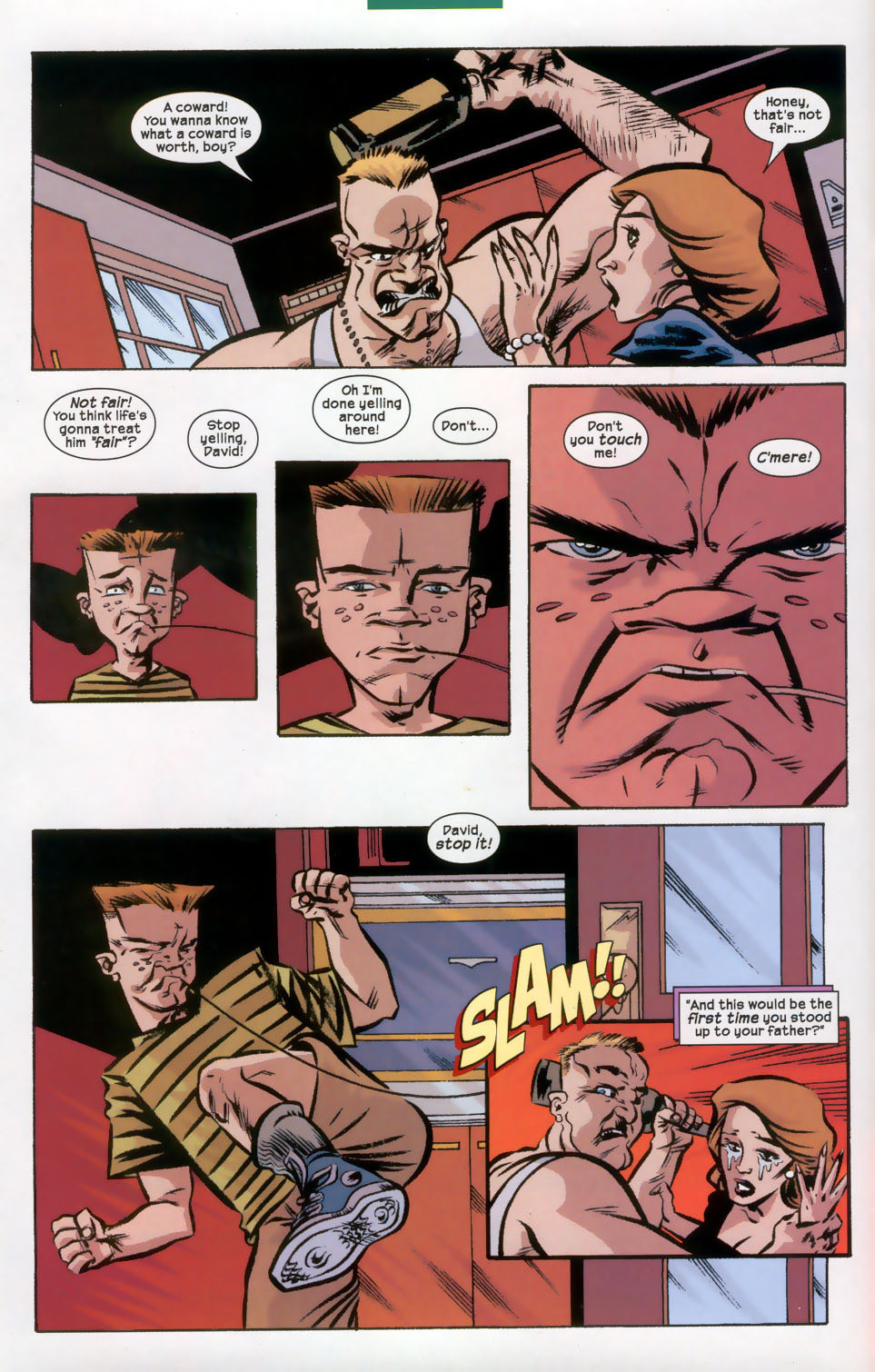

This motivation revolved around Jonah father. Jonah is shaped by his experiences with his father the same way Mary Jane, Flash Thompson, Harry Osborn, Norman Osborn and many other characters are; including Spider-Man himself.

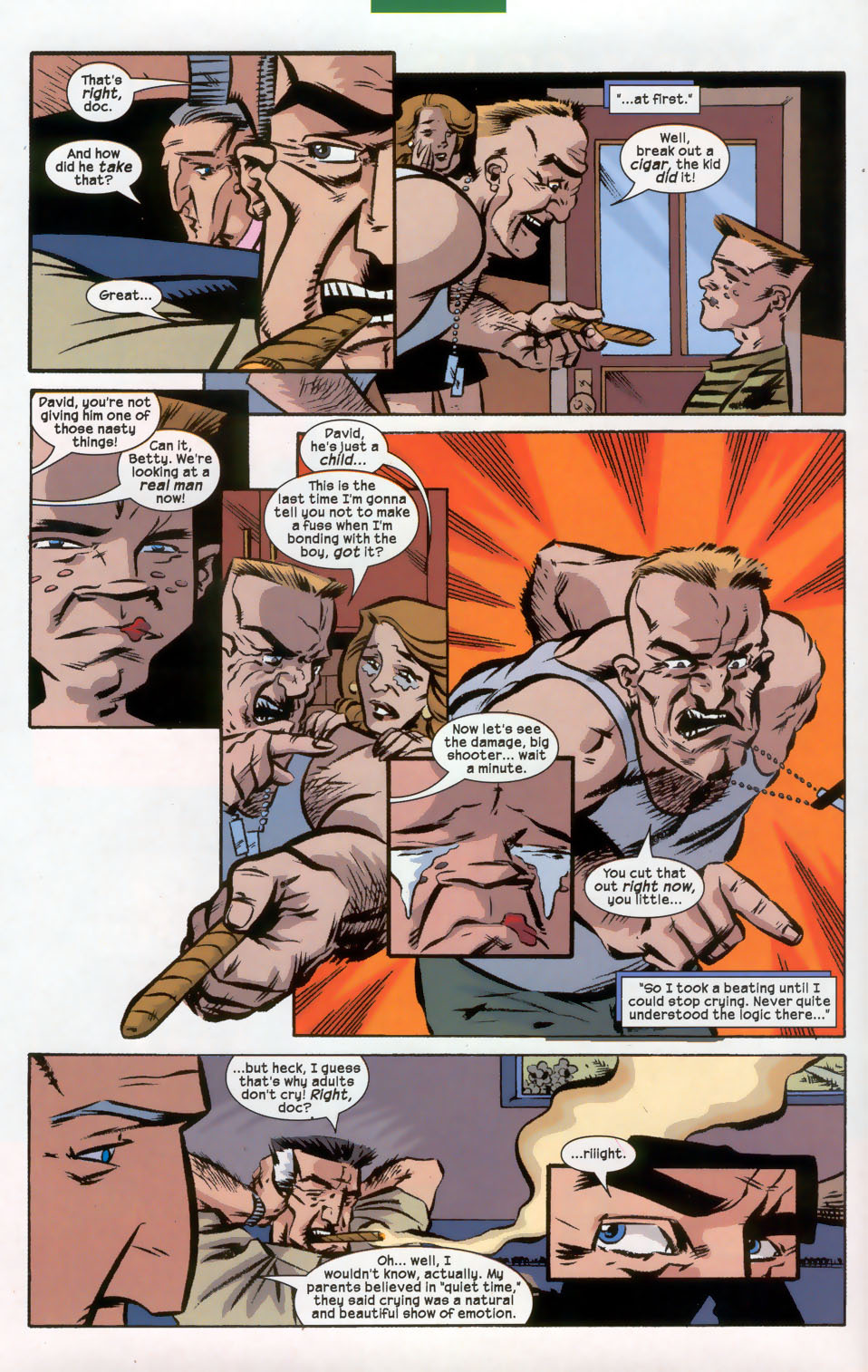

According to Wells Jonah’s hatred of Spider-Man stemmed from both his anonymity and more precisely the fact that he was a hero. Jonah in experiencing abuse at the hands of father (retroactively his uncle/step-father) the war hero developed a mistrust of so called heroes. When Spidey arrived on the scene deep down he presumed him to secretly hurt his loved ones behind closed doors too. In particular since his brand of heroism was bigger, louder and more direct than most conventional forms of heroism like a soldier’s for example.

Jonah simply had to believe the worst of Spider-Man.

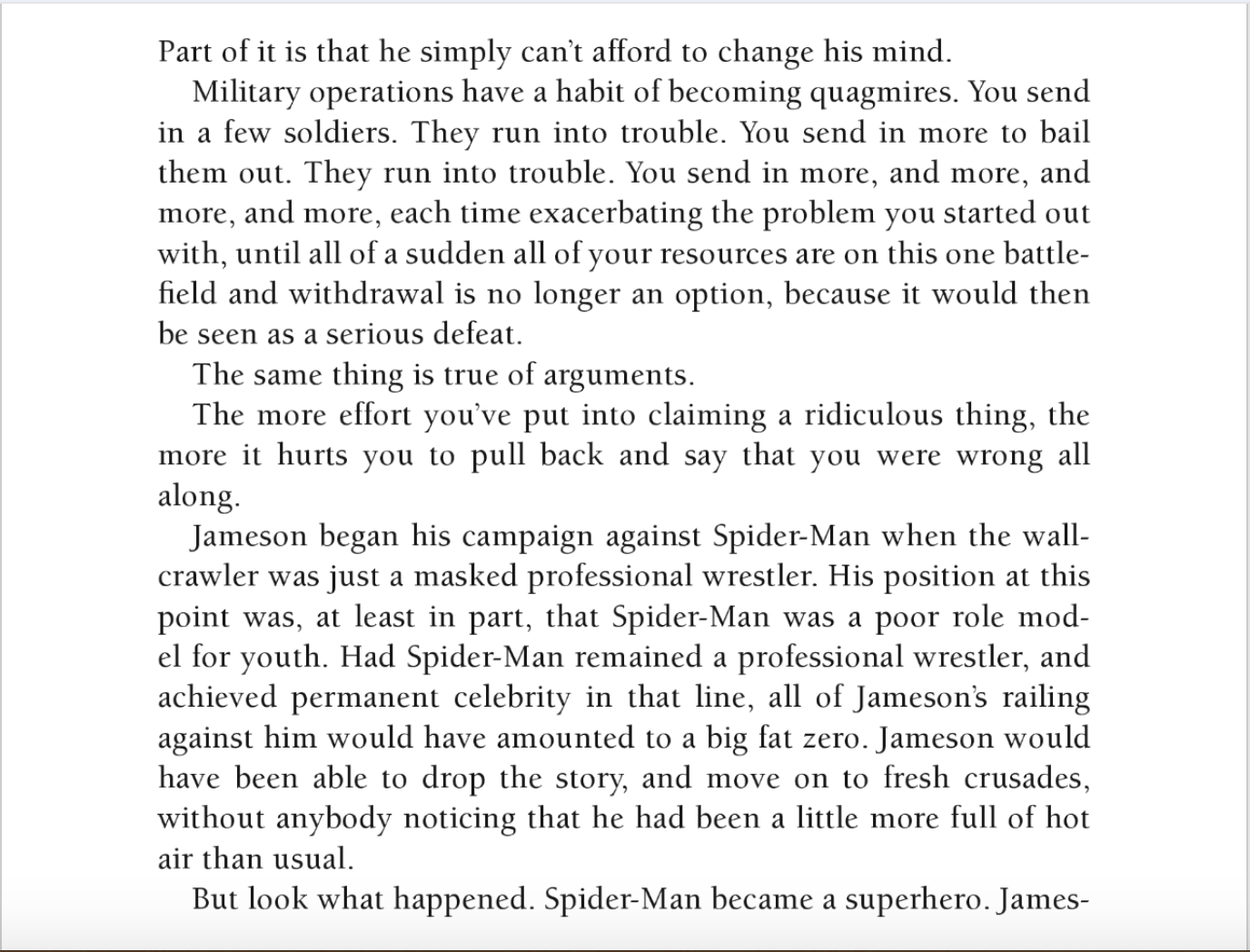

Author Adam-Troy Castro had a different take, one he put forward on two separate occasions. The first was in his (canonically questionable) 2001 novel ‘The Revenge of the Sinister Six‘ and the second was in ‘Webslinger: Unauthorized Essays On Your Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man’; where he cited the former.

In his essay, Castro initially compared Jonah’s vendetta to military operations. The idea being that when an operation goes awry there is a tendency to continuously double down. The end result being that admitting failure and retreating is too painful a process.

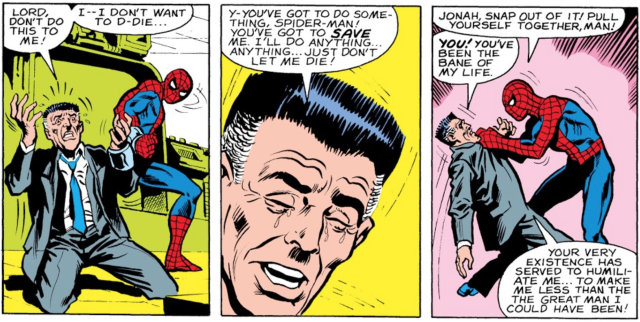

Castro concluded his essay by quoting Abe Saberstein, a crisis counsellor who talked to Spidey in Castro’s novel. Saberstein theorized that on some level Spidey was driven to be heroic to prove Jonah wrong. In turn on some level Jonah continued his vendetta so that Spidey would continue to save him.

Finally Christopher L. Bennet’s (also canonically debatable) novel ‘Spider-Man: Drowned in Thunder’ provides probably the most in depth look at Jonah’s vendetta.

It manages to knit together and expand upon ideas touched upon in almost all the explanations we’ve looked at so far. Since it needs to be seen to be believed I shall simply quote the whole passage.

“…Yeah, I know he thinks he’s a hero, Robbie. And sometimes that means he gets lucky and saves a few lives. But he’s a loose cannon Some mutations or a freak accident gave him, power and he gets his kicks showing off how strong and brave he is by running around town beating up crooks and fellow freaks. Remember, he didn’t start out as a crimefighter. He started out trying to get rich and famous.”

Jameson reflected back on those early days, when a mysterious “Masked Marvel” had had his debut in an exhibition wrestling match, gleefully humiliating his opponent. Within a week, he’d begun making the rounds of the late-night talk shows and monster-truck rallies as “The Amazing Spider-Man,” donning his garishly creepy costume and showing off his strength, his wall-crawling, and the gimmicky webshooters he’d no doubt borrowed or stolen from somewhere.

At the time, Jameson had been only distantly aware of him, finding him pathetic and obnoxious when he could be bothered to spare a thought for this latest fad. But then the news had come in-the self-absorbed punk had horned in on a law-enforcement operation, putting lives at risk by recklessly charging into a warehouse where a gun-toting killer was holding off the police. Only the luck that protects the criminally stupid had enabled Spider-Man to take the gunman down without getting himself or anyone else killed. Ironically, it was the very man who had killed Peter Parker’s uncle just hours before, and Jameson sometimes wondered if some kind of misplaced gratitude had led to Parker’s fascination with photographing the web-slinger. (Indeed, there had been times when he’d idly wondered if Parker himself might be Spider-Man, somehow using an automatic camera to take all those poorly composed photos. But he’d seen them together more than once. Besides Parker’s aunt was a sweet, classy broad-at least up until recently, when she’d changed her tune and started defending Spider-Man’s antics. Senility was a sad thing. Anyway, there was no way a fine woman like that could have raised a disrespectful punk like the wall-crawler.)

In the days that followed, Spider-Man had suddenly begun a crusade against the underworld, even while continuing his show-business ventures. It was then that Jameson had begun to realize how dangerous this man was-this glory hound who only wanted profit from his powers. He had seen that the web-slinger’s pursuit of criminals was just another attempt to grab at fame and fortune by imitating superheroes who had recently begun to emerge. (Indeed Spider-Man had almost immediately made an attempt to join the Fantastic Four, only to abandon that goal when he learned there was no money in the job.) And Jameson knew that someone like that was liable to get people hurt.

So Jameson had begun editorials warning people about the menace of Spider-Man. He couldn’t risk letting the wall-crawler trick the public into thinking he was a hero. Unfortunately, his efforts had backfired; the bad press had made him persona non grata in show business, leaving him free to take up the crimefighting gig full-time. Jameson still wondered if Spider-Man would’ve gotten it out of his system and gone back to show business if he himself hadn’t scuttled the webhead’s career, But if he was responsible for that, it just made it all the more imperative that he be the one to fix it.

“He’s out for glory, Robbie, ” Jameson went on.

“And he doesn’t care how many laws or how much property gets smashed in the process. He thinks he’s above the law, above all of us crawling around down here while he swings by overhead and jeers at us. He’s got nothing to keep him in check, so why shouldn’t he cross the line?”

“Why doesn’t Captain America, or Thor, or Reed Richards?” Robertson asked. “The heroes could’ve conquered this planet a thousand times over if they’d wanted to, and nobody could’ve stopped them. But they don’t because they believe their powers are meant for good”.

Jameson scoffed. “Nobody’s a hero, Robbie. Heroes are just bullies and egotists with good PR. We’ve all got our dark sides, our selfishness and anger and hate.”

“Of course, but we keep it in check.”

“Society keeps us in check. We don’t do the nasty things we all want to do because there are people watching. Because we’ll get punished for it-go to jail, get fired, lose our social standing, get looked at with contempt or disgust by other people. It’s our fear of not getting away with it that keeps us under control.”

He shook his head, thinking of his father the war hero and the unheroic things he did out of the limelight-the drinking, the cheating, the beatings. “But if nobody can see us, if we think we can get away with it, we’ll do anything. For someone who hides behind a mask…someone the police can’t identify, someone whose own friends and family probably don’t know what he does…there are no consequences to face. Nothing to keep him in check. And the longer he can get away with it, the more he likes it, and the farther he’ll go.”

There had been a time, Jameson recalled, when he had been jealous of Spider-Man. The man had actually saved the life of Jameson’s own astronaut son, John, despite the damage Jameson himself had done to his career. Though JJJ had publicly condemned the wall-crawler, blaming him for sabotaging John’s spaceflight in the first place rather than give the impression that he’d been wrong in all his warnings, on some level he’d been grateful. And for awhile, he’d secretly let himself become convinced that Spider-Man was a hero after all, a better man than Jameson because he was willing to risk his life to save others while Jameson was only interested in profits and success.

But that hadn’t lasted. Jameson had striven to improve himself, to prove he wasn’t less of a mensch than the wall-crawler. He’d become a crusader for civil rights and public safety. He’d brought Robbie, the best, most honest newspaperman around, on board to rise the Bugle’s respectability. He’d outgrown his early attempts to send superpowered freaks or Spider-Slayer robots after the webhead, realizing that by doing so he only let himself be dragged down to the arachnid’s level.

And he’d realized something. For all the good he did, he was still doing it in the name of profit, even it was just the personal profit of feeling better about himself about how others thought of him. And that led him to realize something else, too: Spider-Man was no better than he was. Spider-Man had started out as a money-grubber, too. And if J. Jonah Jameson was still a self-serving money-grubber at heart despite all the charitable ventures and heroic crusades he’d undertaken for this city, then Spider-Man must be, too. The only difference was that Jameson showed his face. His own self-interest kept him on the straight and narrow, because he knew the consequences he’d face if he strayed.

He voiced his thoughts to Robbie. “Everyone knows who the Fantastic Four are. A lot of the Avengers don’t have secret identities, and the government knows who the rest are. People like that, people who have the courage to step forward and accept accountability for their actions, can be trusted-at least as far as we can watch them.

“But a superpowered loner practicing vigilante justice in a fright mask? That’s a time bomb waiting to go off, Robbie. He doesn’t have anything to keep him in check.” And without it, Jameson knew sooner or later Spider-Man would do…well, exactly Jameson himself would do if he thought if he thought he could get away with it. Do what he wanted, and beat down anyone who stood in his way.

Jameson would never tell Robbie-would never tell anyone-but that was the real reason he hated and feared Spider-Man: because he understood him. Because he knew that, deep down, they were the same.

Heaven help them both.

Whilst I somewhat question the novel explaining away the jealousy motivation, I love pretty much everything else about this.

Most of all I like the way it puts across Jonah’s origin in Tangled Web #20. In his mind Spider-Man is reckless yet claims to be a hero. But he also hides his identity, which to JJJ is tantamount to admitting he is like his abusive father. Jonah’s obsession is thus really him indirectly striking out against his abusive father and his hypocrisy. This neatly explains why Jonah has gone to such incredible extremes against Spider-Man. Jonah himself (as his origin story demonstrated) when he has something to prove or is pushed to it doesn’t do things by half measures and was clearly damaged by his father’s upbringing. Thus he was unlikely to curtail his vendetta (stemming from his deep seated Daddy issues) instead taking it way too far.

At the same time though he truly believes he is doing something beneficial for everyone. He feels Spider-Man needs to be held accountable or else nothing would stop the wall-crawler going too far himself. This touches upon how Jonah’s father behind closed doors didn’t care what he did and how Jonah believed he personally would also abuse power if not for ‘society’ keeping him in check.

This sadly mostly removes the jealousy motivation, but the trade off is that Jonah’s character not only makes complete sense but ties more directly into some of the fundamental themes of the Spider-Man series.

Spider-Man is a hero motivated by the belief (gifted to him by his father figure) that his power obligates him to use it responsibly. To do that effectively and be responsible to his loved ones he needs to wear a mask.***

And yet in being a hero and wearing a mask he makes his life and heroic activities all the harder (and less gratifying) because Jonah will inevitably pursue him because otherwise (according to Jonah) Spidey would obviously use his power irresponsibly.

This is a belief Jonah holds because his own father was a ‘hero’ who had power over him and abused it unheroically thanks to the anonymity of his own home. Jonah’s father effectively taught him that those with power will inevitably be irresponsible with it unless held accountable.

At the same Jonah knows if he was in Spider-Man’s position he definitely would be abuse his power. Thus he sees it as his own responsibility to hold Spider-Man accountable and stop him. An act that ironically results in him using his own power irresponsibly through libel. And all this is because he is working through his own issues with own irresponsible father.

At the end of the day it all comes back to the fundamental ‘Power and Responsibility’ concept.

And I’d say that is a pretty good motivation for Spider-Man’s oldest enemy.

*Although that being said the FF are in fact in ASM #1 as well.

**It should be noted Jonah made certain exceptions for some heroes, like Captain America, whilst reserving a special kind of hatred for Spider-Man.

***Masks themselves are another theme in Spider-Man. See Norman Osborn and Mary Jane.

I prefer Spider-Man and Jonah’s current relationship in the 616 comic books.

Awesome in depth article, nicely done … It says quite a bit abou the nature and timelessness of this character and how even today Pundit Media Mogals still exist … I wonder was JJJ someones hero when they were growing up?

I actually bought that book under the impression that every essay was by JR! To be fair, I still enjoyed them all, so I didn’t exactly feel cheated, I like to keep it in my bathroom as some handy reading material (not as toilet paper… except that one time!)

@Alex – As JR explained, it’s a running joke on the podcast (or at least it was years ago) that everyone would say it was “J.R.’s book” even thought he was one of many contributors.

You are correct Alex. I had nothing to do with that book but my own essay, but everyone on the site has had a lot of fun over the years calling it “my” book. It’s like me getting credit for “fixing” Sins Past and fitting it into canon, when really the only thing that was officially lifted from my essay was that “Gwen went to visit Norman Osborn to say thank you for rescuing her.”

@hornacek

The book was a collection of essays edited by Gerry Conway. JR was one of several contributors but was not the editor and to my understanding was uninvolved in anything in the book beyond his own essay.

Prior to each essay Conway gave a forward with his own thoughts on the subject of the respective essays and in Troy-Castro’s Jonah essay he drew the Wertham comparison.

“but is an observation made by iconic Spider-Man writer Gerry Conway in the J.R. Fettinger’s 2006 essay book ‘Webslinger: Unauthorized Essays On Your Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man ’.”

Fixed it for you.

@ William Sinclair

a) You are most welcome

b) ‘Drowned in Thunder’ sort of knits together the various explanations for Jonah’s animosity

c) Much like Legends of the Dark Knight, Tangled Webs exists as a schrodinger’s cat situation. The stories were not non-canonical but they also weren’t as canonical as the stuff from say ASM until an ASM issue confirmed it as such

d) Tangled Web #20 has been confirmed as canon at least twice, most recently by Spencer himself

@William Sinclair. You are most welcome.

I think Bennet actually utilized your explanation of everything being true.

Tangled Webs is Schrodinger’s canon. it isn’t necessarily non-canon but it’s not canon enough for anything else to be beholden to it. It is not dissimilar to the Batman series Legends of the Dark Knight where stories were only firmly in canon if the other main titles said so. But Jonah’s origin from the series is most definitely canonical now.

Thank you for this great article about my favourite Spidey supporting character! I guess I kind of reconcile a lot of the inconsistencies with Jonah’s motivations by telling myself that the various different explanations for the hatred are all equally true and kind of pile up in his subconscious. I liked how Spencer pointed out just how often Spidey liked to antagonise him too, I think that must have exacerbated it all for him, especially since he probably didn’t realise that Spidey was a teenager acting out early on instead of a fully grown man. Tangled Web #20 is probably my favourite Jameson story overall and it’s probably the most compelling motivation to me, though everyone tells me it isn’t canon (I know the Tangled Web series played loose with continuity, but I think you can fit most of it into canon pretty easily, personally.) I guess the most understandable and straightforward motivation is in the Ultimate continuity, where he’s bitter that Spidey took attention away from his son’s death. That version of Jonah is definitely the most consistent and has a nice arc, but I do prefer the sheer entertainment value of 616 Jonah.