This is a revised version of an article I wrote to coincide with the Ultimate End mini-series. It seems appropriate to bring it back, now that Bendis is coming to another end, as his tenure at Marvel has reached its conclusion—for now—and he’s going off to the distinguished competition.

He’s arguably been Marvel’s biggest writer since Ultimate Spider-Man #1 came out. I would go so far as to call it not just the most important Spider-Man comic book of the last twenty years, but the most significant American comic book of the last twenty years. The only reason it’s not the most important comic book of the 21st Century is that since Ultimate Spider-Man #1 came out in October 2000, it technically missed the cutoff for the 21st Century by a few months.

Bendis wasn’t the first choice to write the title. Howard Mackie turned it down, a decision that may very well have changed modern comics. At that point, Bendis was an acclaimed but obscure writer/artist of crime books. He had recently realized that editors were more interested in his writing than his art, and had raised his profile a little bit as he worked on more titles, including two Spawn spinoffs—one about cops in a superhero universe—as well as a fill-in arc of Daredevil, about a crime reporter in a superhero universe. He had also just started on Powers, a creator-owned project with Mike Oeming about cops in a superhero universe. A retelling of the Lee/ Ditko Spider-Man comics appeared to be outside his wheelhouse.

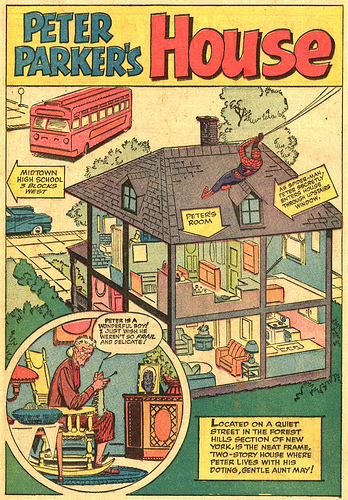

Bendis worked on the book for over 160 issues with the teenage Peter Parker as the lead. Artist Mark Bagley stuck around for 110 issues, longer than Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four run. The take on Peter Parker in the Ultimate comics would inform adaptations of the Spider-Man comics in other media. There is the obvious influence on the Ultimate Spider-Man cartoon, while aspects of the series were used in the Marc Webb and Andrew Garfield Amazing Spider-Man films, including Peter Parker telling his girlfriend his secret identity, his girlfriend helping him with a gunshot wound, and Peter investigating the mysterious deaths of his scientist parents. At this point, I should make the obligatory reminder than influence isn’t always positive. Jon Watts—director of the MCU Spider-Man film—has cited the series as a major influence for his adaptation of the character, which makes sense, since it’s a well-regarded run about a teenage Peter Parker, and he’s going to do some films about Peter Parker in high school.

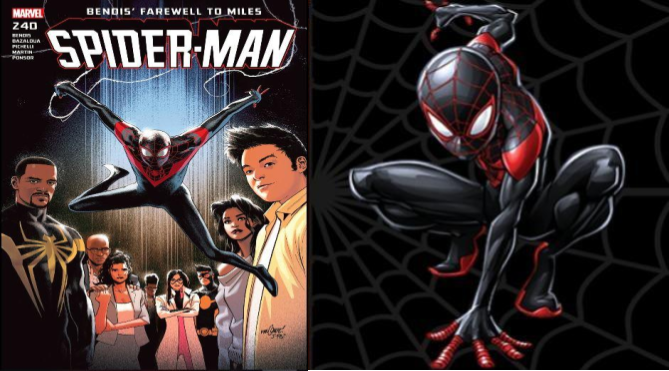

Bendis would follow the early issues of Ultimate Spider-Man with a run on Daredevil, which outed the character, and paved the way for the runs of Brubaker and Waid. He’d launch Marvel MAX with Alias, the series that introduced Jessica Jones, star of the Netflix show. He’d have one of the longest runs in Avengers history, cementing an idea that seemed to be forgotten after Avengers #16 that this title wasn’t meant to be its own corner of the Marvel Universe, but a book all types of Marvel characters could pop up in. Event books House of M, Secret Invasion, Siege and Avengers VS X-Men would all build from the Avengers run. All-New X-Men brought the original five X-Men to the Marvel Universe as teenagers freaked out about the adults they became, and other writers have kept that concept. Guardians of the Galaxy revived that franchise in time for the film. His Iron Man run introduced Riri Williams. Spider-Man brought Miles Morales to the classic Marvel Universe.

Bendis was prolific, and had his fingers in multiple corners of the Marvel Universe, building on the success of his early projects to become one of Marvel’s most important writers ever. It’s possible to make the case that he was their most important writer since Stan Lee. This claim is going to require some explanation and caveats. It doesn’t require his influence to be on the level of Stan Lee, since no one comes close. It doesn’t require him to be as important to comics as someone like Frank Miller, as much of Miller’s groundbreaking work was done for other companies (Ronin, Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One for DC; Sin City and 300 for Dark Horse.) His main competition would probably be Roy Thomas and Chris Claremont. Much of Roy Thomas’ most important work was in licensed comics, which would have less impact on other Marvel titles, while Claremont worked primarily in the X-Men line, transforming it significantly, even if Wolverine and the international X-Men were created by Len Wein.

Because early issues of Ultimate Spider-Man sold out, the Ultimate brand had a positive reputation just in time for the debut of Ultimate X-Men. It’s not the only reason that book was a hit, but it definitely made it an easier sell. That helped make Mark Millar’s reputation, helping him with his later creator-owned projects. Millar would take a gamble on The Ultimates, that universe’s version of the Avengers, which would become the basis for the Marvel Cinematic Universe versions of Iron Man and the rest of Earth’s Mightiest Heroes. The Ultimate versions of Marvel’s first family would serve as the basis for Josh Trank’s Fantastic Four film (again, influence isn’t always positive.) The Ultimate Universe did come to an end fifteen years later, although part of it is that the emphasis on accessibility spread to other Marvel titles, so it didn’t serve the purpose it once did. At this point, the rest of the Marvel Universe has become more like the Ultimate comics.

These issues had a cinematic style that other comics would soon strive to replicate. This is now the norm in comics, described as writing for the trade, decompressed storytelling, or widescreen comics. The early issue had a manga-esque pace as five pages could be devoted to mood and characterization as Peter Parker has lunch alone in a mall, until Uncle Ben arrives and calls MJ over. There were no thought balloons, or even narration captions, although Bendis would incorporate those in the next issue. The rigid grid structure kept the book easy to follow, helping make this an obvious title to hand someone who hasn’t read a lot of comic books, and might not be able to follow more complicated storytelling.

Every issue of Ultimate Spider-Man would be collected in trade paperback form, something that changed how Marvel —and soon enough DC—made money, and how readers experienced comics. Marvel would soon hire a writer for Amazing Spider-Man who had a cinematic style, whose work didn’t depend on readers being familiar with prior continuity, and whose entire run would be collected in trade paperback format. The Brand New Day era would have a shorter storylines, as a response to the sense that comics were written for the trade, although that still suggests the influence of the comic that kicked off the style a new run was meant to provide an alternative to.

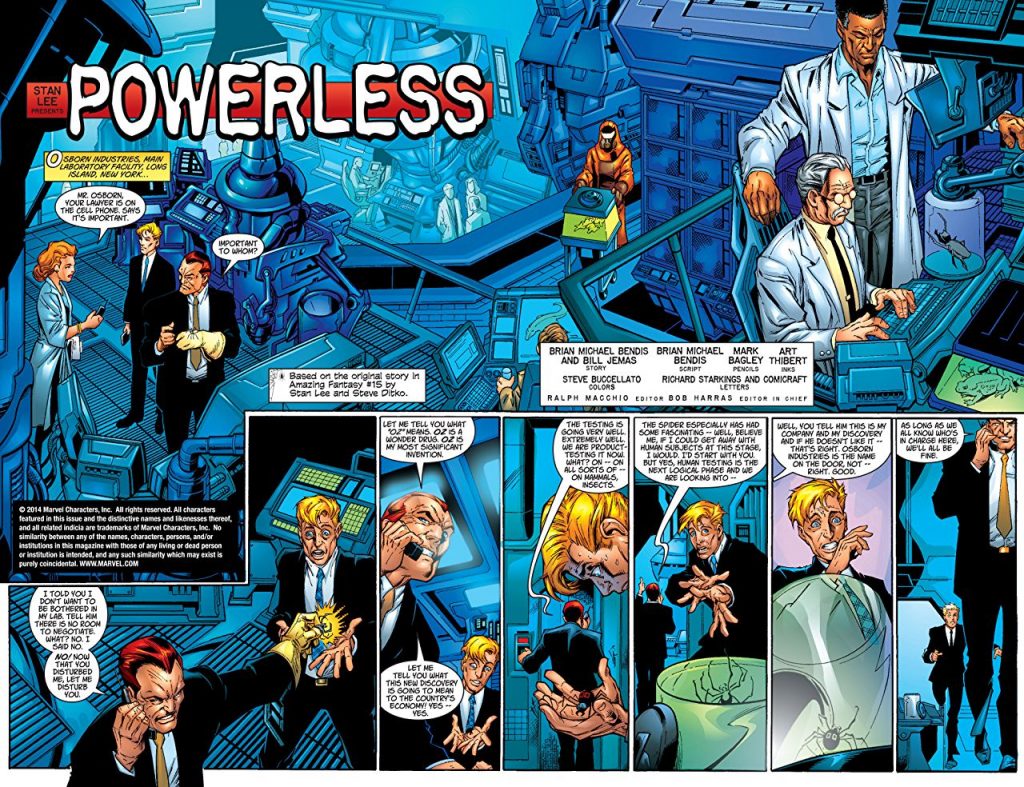

The first issue was 48 pages, but Peter Parker wouldn’t wear the costume until the end of the third issue. Bendis and Bagley were aware that they could have a new spin on one of the most famous superhero origins by exploring it in more depth than ever before, so that when Uncle Ben is murdered—at the end of Issue 4—the readers care. This wasn’t necessarily a complete innovation. Spider-Man 2099 #1 ended before Miguel O’Hara had donned his costume, although as most of the issue was a flashback, Peter David and Rick Leonardi did feature the conventional scenes of the new superhero in action in the first pages. Kevin Smith and Joe Quesada’s Marvel Knights Daredevil had a slower pace, although it was heavy on narration, and the run lasted for the length of one trade paperback. The first issue of the Valiant Comics revamp of Solar Man of the Atom didn’t really give readers a sense of what later issues of the comic book would be like. Generally, it’s not unusual for developments in independent comics to trickle down to Marvel and DC over the source of several years and decades.

Some of the copycats weren’t successful. Robert Kirkman did an attempt at a Sleepwalker reboot for the Epic Comics anthology, which had a slow build and last page revelation about the protagonist’s mystery. However, he lacked an artist on the level of Mark Bagley, the knowledge readers have that the young character we’re devoting a lot of time to will soon become rather interesting, and an opening as compelling. Marvel’s Tsunami line also had TPB length origin stories. Brian K Vaughan and Adrian Alphonso’s Runaways is fondly remembered. Human Torch and Namor, not so much.

For all the talk of writing for the trade, Bendis did make sure that this issue wasn’t just set-up. There was a scene where Norman Osborn—concerned that the spider bite was going to kill Peter Parker, and leave him very vulnerable to a lawsuit—hires a hitman to take care of the problem. The attempt on Peter’s life occurs in the first issue, and leads to early displays of the spider powers. Peter and MJ also grow a little bit closer, first thanks to Uncle Ben’s intervention, and then sharing a moment on the bus after the spider bites Peter. The issue ends with Peter realizing just how much he has transformed.

Maybe if things had gone differently—if Howard Mackie had been the writer of Ultimate Spider-Man #1 and bombed—the comics market would have been in essentially the same place. The trade paperback market would certainly still have been discovered. Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Millar would probably have become star writers, although the breakthrough projects would likely be different. Adaptations of Peter Parker might still explore his high school days, although this is the least certain without over a hundred issues of modern style comics with a teenager Peter Parker. Even if everything else would have happened, this was the comic that helped it all happen a little bit faster. Even if it wasn’t responsible for comics going in a particular direction, it’s the issue that represents the realization of these major trends.

Bendis’ recent work for Marvel hasn’t been as important, but it is a big deal that he’s going to DC. He had done 70+ issues on Daredevil, Spider-Man, the Avengers and the X-Men, while introducing Miles Morales and Jessica Jones, so reaching those heights all the time was unlikely. His main options were to return to characters he had tackled before (as in the Jessica Jones and Defenders series) or to work on series that weren’t his first choice (He play-acted Avengers issues with his brother when he was a kid; I kinda doubt he did the same with Guardians of the Galaxy.) At DC, he’ll be able to take on the biggest icons in comics, as well as slightly more obscure favorites that he’s wanted to work on for years (like Plastic Man.) It’s a big move for both Bendis and DC.

So, what do you guys think? Am I overstating the significance of Bendis and this one comic? Are there other comics that are more important? Do you think the influence of the book is positive, or negative?

While it is certainly arguable that the success of ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN led to some of the unpopular changes in the 616 continuity, I can’t deny that it’s a really solid take on the character and just an all around great series in general. Good article, Mets.

I’ll give you that this issue is one of the most important in the last several years. It helped Marvel out of bankrupcy, started a new successful line at Marvel and it started the trade model which is used today. I tried of thinking of a bigger comic since 2000 and I can’t think of one. Well written article as always.