The U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments today on a case involving a patent for a Spider-Man toy.

The U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments today on a case involving a patent for a Spider-Man toy.

The case is Kimble vs. Marvel Enterprises, Inc. Constitution Daily’s Laura Beltz explains it thus:

When a company buys the licensing rights for a web-slinging toy, does it need to pay royalties to the inventor forever? Or just until the toy’s patent expires? The Supreme Court has already answered this question, but an upcoming decision from the Court may overrule a 50-year precedent.

The Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments in Kimble v. Marvel on Tuesday and it could decide to overturn its 1964 decision in Brulotte v. Thys Co.The ruling in Brulotte is clear; that isn’t the problem. The Court held that “a patentee’s use of a royalty agreement that projects beyond the expiration date of the patent is unlawful per se.” This simply means that once a patent expires, the patent holder doesn’t have to pay royalty fees to the original inventor when using it.

The Kimble case is, then, an easy one if the Court were to simply apply the Brulotte standard.

In a settlement agreement out of prior litigation with Marvel Enterprises, Stephen Kimble assigned his patent for a toy with Spider-Man’s web-shooting power to Marvel, and Marvel agreed to pay annual royalties if it made its own web-shooting toy. In 2010 Kimble’s patent expired, and Marvel stopped paying royalties.

To apply Brulotte to these facts, all a court needs to do is read the contract between the parties and determine whether royalties following the expiration of the patent were agreed to or not. Applying the rule of law is not the problem.

The problem, then, is that the Brulotte has been widely unpopular, and Kimble is not alone in moving to challenge it.

More below the fold…

Ars Technica’s Joe Mullin describes the toy and goes into a bit more detail on the legal problems between Stephen Kimble and Marvel:

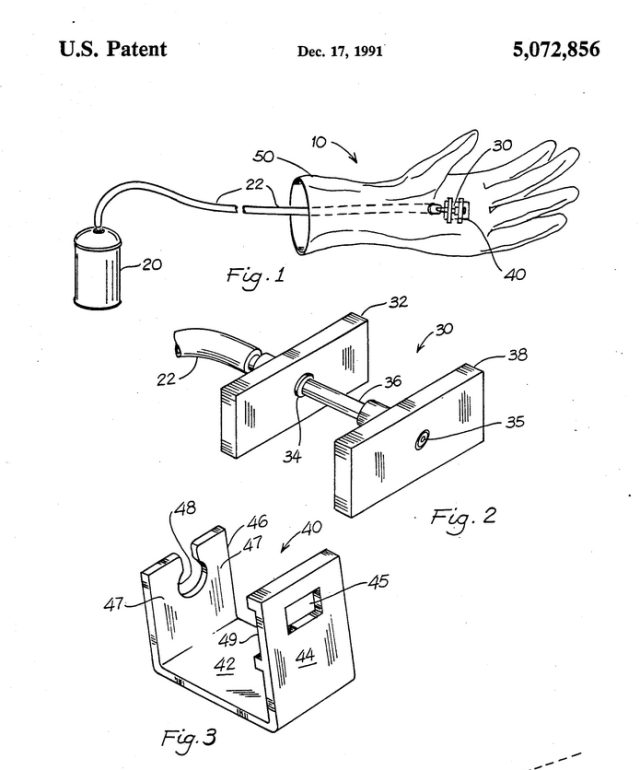

Stephen Kimble invented a toy “for shooting string foam” in 1990, and he patented it as US Patent No. 5,072,856. The device envisaged is a glove that shoots foam from the palm “to create a spider-like web for amusement purposes.”

In December of that year, he met with the president of Toy Biz, Inc. (now part of Marvel Enterprises) to discuss his then-pending patent and offer them “ideas and know-how” related to the toy. According to Kimble, the president verbally agreed he’d compensate Kimble if the company used his ideas.

In 1997, Kimble sued Toy Biz for patent infringement and breach of contract, saying that a toy called the Web Blaster was a rip off of his idea. The district court found that the Web Blaster didn’t infringe Kimble’s patent, but it sent the allegation that Toy Biz had broken an oral contract formed at the 1990 meeting to a jury. The jury found for Kimble.

Both parties appealed and settled the case in 2001 while the appeals were pending. Marvel agreed to pay $516,000 plus three percent of “net product sales” to Kimble and his lawyer, Robert Grabb, who had become a co-owner of the patent. The deal wasn’t a traditional patent license in that it actually transferred the patent to Marvel. It also—problematically—didn’t specify an end date.

Kimble and Grabb were paid more than $6 million over the years. Later, Marvel began making other kinds of toys similar to the Web Blaster. Kimble and Grabb said the new products infringed their patent; Marvel disagreed and stopped paying. Kimble sued Marvel in 2008, saying the settlement had been breached.

Marvel fired back, saying that it didn’t owe royalties on the new products. In any case, the company believed it couldn’t be made to pay royalties past the life of the patent under a 1964 case called Brulotte v. Thys Co. The argument that Brulotte was controlling was a slam-dunk, and Marvel won victories in district court and again on appeal.

But now Kimble has one more chance to win his case. His lawyers have filed a petition asking the Supreme Court to overturn Brulotte altogether, calling it the “product of a bygone era” and “the most widely criticized of this Court’s intellectual property and competition law decisions.”

As with many Supreme Court cases it could take months before the court’s decision is actually released to the public. If you’re still interested in learning more about the case, check out SCOTUSBlog.

–George Berryman!