In the comic book realm of superheroes, few characters possess the hard-earned reputation of having a steady chronological run that crosses decades – and generations of readers who have committed to growing up with the ever-turbulent life of Peter Parker and his world-famous alter-ego, The Amazing Spider-Man.

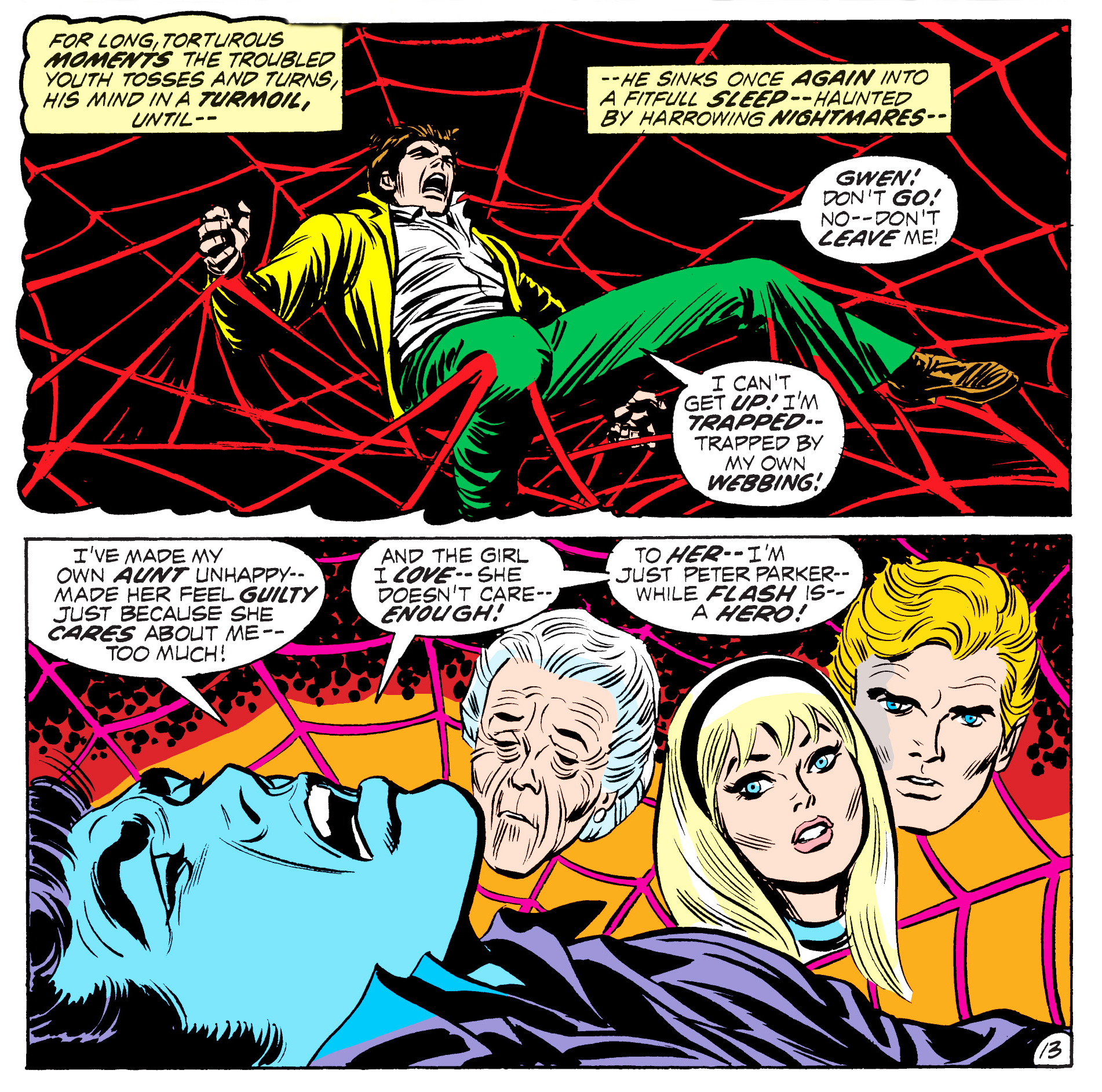

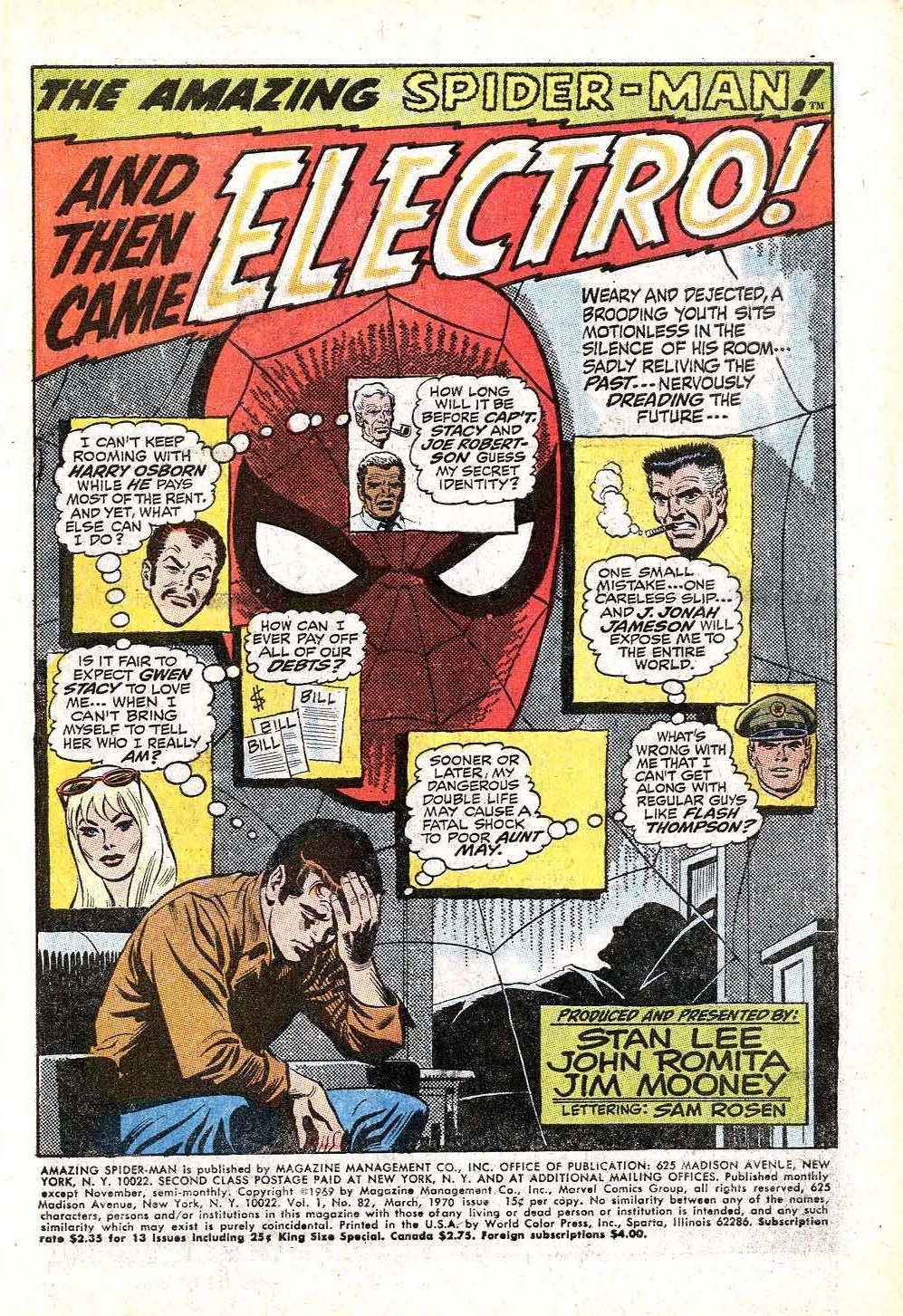

His life, his adventures, his inner conflicts, the near impossible-to-bear learning curve, his growth, his passions, fears, and iconic sense of humor, his victories, defeats, and forever-felt losses. To this day and age, the character still stands as the ultimate depiction of how a young guy in the real world would behave were he to become a superhero: his private life would be a mess, and the caution to protect his secret identity would be the fuel to many nightmares to come, coated with sleep deprivation; his relationships would be limited, and to protect his loved ones from possible enemies looking for a payback, they could never learn his secret. And the ones who could, their lives wouldn’t be easy either, just for the sake of keeping his secret. It’s not only about power and responsibility but also consequences – unintended or not. But why should any superhero be burdened with all of these psychological and emotional problems just to protect his secret identity? The character’s premise is to depict the bad side of being a superhero, masterfully conceived by his creators Stan Lee & Steve Ditko -, lies in one element: his age. He’s the unsupervised orphan teenager without an instruction manual on how to be a superhero. During the entire run (sometimes fully) plotted and drawn by Ditko, Peter Parker was shown many times over on the verge of a mental breakdown, though fortunately able to blow off some steam while under the mask and fighting supervillains. Whatever recklessness fueled by subtle hints of neurosis could eventually affect those around his life.

So any normal relationship with a woman – not even including a best friend, or familiar to confide his secret life – would not be possible. This kid had yet to learn how to be a man, a responsible adult. He would have to learn to reconcile both parts of his life without either affecting the other.

Once again, due to consequences.

With that said, consider the mother of all damsels in distress in superhero comics: Lois Lane. She has never “died” (for real) in her comics’ continuity, because Superman was always there to save her; an unwritten rule. Saving the girl was – until then – the ultimate proof that heroes could not fail. Having this rule broken was unthinkable; killing the hero’s love interest – or any constant supporting character – would only leave the readers people in shock.

Superman is also the ultimate representation of a flawless and responsible adult, therefore failing to save Lois would be admitting that The Man of Steel could be flawed like any other person.

Ultimately, Peter Parker is the hero who could be any of us. And in any form of fiction, a character like that is a well of gold. It’s no wonder he is known all over the planet as one of the benchmarks of superhero iconography. And such a reputation – especially in the character’s publication history – doesn’t come without milestones that defined his history: most of his victories remain invisible to public knowledge; his losses are embellished with personal drama, shock, and even death. His very origin is shaped as such.

The most tragic one, not only became the definition of villain vengeance against his nemesis but also the landmark of the end of an era in the comic book industry itself: the end of the Silver Age of the Comic Book industry, ushering the way to the Bronze Age. 51 years ago, Gwen Stacy died and the Superhero comics changed forever. They evolved.

More info on the Comic Book Ages can be found here on our website – courtesy of the great Thomas Mets, a great Spider-historian.

THE GWEN STACY PARADIGM:

As seen from his first appearance on the 15th issue of the Amazing Fantasy comic, this reckless kid had to learn how and why to be a hero by downright lack of responsibility. Self-absorbed in his guilt, he had to grow up earlier and faster into the man he was never prepared to be. With the loss of his only father figure and thrown into (the real) life of troubles and concerns that none of his colleagues had, he had no choice but to set and adjust himself to make money to make ends meet at home, take care of his sick old Aunt, build himself to be a successful adult in science and still fighting evil and crime under the guise and the alias of a “Man” – the Spider-Man – so that no one else would have to go through the loss he did.

Summing it all up, it’s easy to conclude his Love life would be chaotic, to say the least.

If going to University is the first step of becoming a man – and for some, finding true Love -, Lee & Ditko didn’t disappoint their readers: September 1965 brought the first appearance of Peter’s first on ASM #31: Gwendolyn Stacy – one of the most famous characters in superhero comics lore who’s become more of a legend dead more than the time she was (fictionally) alive. Spider-Man readers and fans alike all know her story – especially her end.

Who would have thought that such a character – whom Peter unknowingly brushed off twice (hey, check the comic!) – was destined to be the woman who set a newer and harder standard of power, responsibility, and guilt in his life?

It’s easy to look back at her history as a character and conclude that her time as a supporting member couldn’t have lasted longer – especially with all the gravitas and weight that Mary Jane Watson was bringing to the table. Readers at the time were noticing – everyone else in the cast was evolving, as Gwen would be relegated to the constant worrisome girlfriend who could never learn about Peter’s life as Spider-Man. She hated the masked hero.

The beauty of The Amazing Spider-Man comic – and subsequent tragedy – was that at the time it was constantly pushing emotional and even psychological boundaries on the “realistic side” of superheroics. Batman and Superman made it all easy, but not in the Marvel Universe, and especially not for Peter Parker; that’s why the comic matters so much. Therefore looking back now, her demise makes sense – all for the sake of the evolution of the main character.

By following a long and even unplanned plot thread, it all started in ASM #90: Capt. George Stacy dies – which propels Gwen to move to London at the request of her uncle in ASM #93, so she won’t be alone anymore – which coincides with Peter’s keeping her at arm’s reach, confused and guilt-ridden for what happened to her father. Looking back on how Peter – even unwillingly – treated her, Gwen had all the reasons to be away from this lousy boyfriend who was always distant and rarely available whenever she needed him the most.

By issues #96-97 Harry begins taking drugs due to MJ’s constant rejection. Norman Osborn returns as the Green Goblin, and Peter defeats him by showing his sick son at the hospital. On ASM #98, Gwen returns, realizing that, despite it all, Peter is her true Love and she wants to be with him.

In superhero chronology, a lot can happen in five months.

It’s not a leap in logic to assume Marvel editorial (at the time) was still deciding what to do with the girlfriend who didn’t know about her boyfriend’s secret identity; if that came to pass, that would have destroyed their relationship, thus making Gwen a liability in Peter’s life. For this reason, why not attempt different approaches? After scribing #ASM 100, Stan Lee handled the script duties to Roy Thomas; the renowned Avengers and Conan The Barbarian writer would venture into the title for just four issues, but not before a superhero comic trope experiment: ASM #103 is Gwen’s tryout as a possible and constant Spider-Man’s damsel in distress, just like Lois Lane – a plot idea suggested by none than Gil Kane, to pay homage to the King Kong movie.

So Peter, Gwen, and JJJ (!) embarked on a trip to the Savage Land to investigate the existence of a strange and unique monster; sounds familiar?

Gwen even gets kidnapped by the Gog monster – just like in the movie! – only to be delivered to Kraven The Hunter. Though a fun adventure to shake up the pace of the title, it didn’t look quite the standard Spider-Man comic: Gwen in a bikini (yay!), Peter fires a gun (whoa!), JJJ cries over the alleged death of Peter (wow!), and more crazy stuff. The tale feels like a filler, and veers too much from Spidey’s usual habitat and Modus Operandi.

But it did prove a point: not by the lack of trying, Gwen Stacy didn’t fit the guise of the girlfriend in danger.

Stan Lee then returns to the title and so it goes until issue ASM #110, marking the last time he would write the character until much later. Gerry Conway takes the reigns as of issue #111 (May 1972), also with Kraven as the main antagonist.

SIDE NOTE: According to this interview by Mark Millar (by the 23:00″ mark), Conway confirms he was first offered Spider-Man because Roy Thomas didn’t want to write him.

One year later (1973), the newly appointed The Amazing Spider-Man writer decided to break a superhero comic book rule, though not by himself.

From the intro titled “Turning Point”, presented in The Marvel Masterworks – The Amazing Spider-Man #13 collection, Conway cites how this event came to pass:

Here’s how some of it went down, as best as I can recall, looking back through the distorted rearview mirror of memory.

When I first started scripting Amazing Spider-Man, I was Padawan to John Romita’s Jedi Master. My name came second in the credits (one of the few times I recall a writer’s credit following that of an artist), a true reflection of my role in our collaboration during those first half dozen or so stories. John taught me how to structure a Spider-Man story, balancing character development, plot, issue-to-issue continuity, and action. He also taught me, that the greater the emotional stakes for our heroes, the more impact a story had. At that point, John had worked on Spider-Man longer than anyone except Stan. He understood the characters better than anyone.

And he wanted to kill Aunt May.

John felt – we all felt, Stan and Roy Thomas (then editor-in-chief), and yours truly – that Spider-Man ‘s life had become too placid, too safe, too… Normal. Despite some terrific individual stories over the previous few years (the drug issue, Captain Stacy’s death, the introduction of the Kingpin) we had a sense that Peter’s life had settled into a, well, rut. He faced villains; he was misunderstood by society; he had minor problems – but come right down to it, things were going pretty well for our friendly neighborhood web-slinger. It was time to shake things up. John believed somebody had to die, to remind the reader (and Peter) that the world was a harsh place, heroes couldn’t save everyone, and sometimes death could not be escaped.

Killing Aunt May, John thought, would accomplish all those goals. And he was right Aunt May was the logical choice, by reason of age, and because her constant near-bouts with death had become a cliche. Killing May would be unexpected: fans would be surprised we finally pulled the plug on the old lady. Tears would be shed.

And life as Peter knew it would go on.

See, that bothered me: killing Aunt May, while upsetting for Peter, wouldn’t shake things up. Peter would still have a fairly normal life. Old people do die, after all. There’s nothing unusual about that. Sad, yes. Tragic, no.

And Peter Parker, in my view, was all about the tragedy.

So I offered up a different victim, one whose death would be even more unexpected than May Parker’s: Peter’s girlfriend, Gwen Stacy.

Now, this may surprise those of you who assume the firestorm of fan disapproval that followed Gwen’s death was something we anticipated and planned for, but the truth is, nobody-not Stan, not John, not Roy nobody thought this was a Big Idea. After all, Gwen wasn’t Peter’s first love interest-that was Betty Brant; he’d even had a flirtation with Liz Allen in high school; and Mary Jane Watson was always flouncing around the fringe of Peter’s romantic interest. Unlike say, Lois Lane, Gwen Stacy hadn’t been a fixture in Spider Man’s life since day one. She appeared three years into the series, and the series, as I’ve already pointed out, was only ten years old.

So, killing Gwen Stacy, while certainly an intense emotional experience, didn’t seem to us to be all that radical a notion.

The general reaction around the office was the editorial equivalent of a shrug; sure, sounds fine, let’s do it.

And maybe, if I’d just let the Goblin throw her off the Brooklyn/Washington/Williamsburg/Queensboro Bridge and put the whole blame on the bad guy, maybe the fans wouldn’t have reacted the way they did.

And maybe comics wouldn’t have changed forever. But I just couldn’t leave well enough alone.

(…)

So when it came time for Spider-Man to save the girl he loved from certain death, it seemed to me only natural that he fail.

But even that wasn’t enough.

As I looked at Gil’s pencils, his beautiful and almost balletic rendering of Gwen’s fall, and Spidey’s desperate but vain effort to rescue her, I was struck by two things:

One… It just didn’t seem dramatic enough. Two…It sure looked like she ought to survive.

Characters bad fallen from greater heights in comics and been caught without injury. So why couldn’t Gwen survive a fall like this?

Well, I thought, maybe she was already dead when the Goblin tossed her. But if she were already dead, that would make Peter’s rescue attempt pointless, even pathetic: the opposite of tragic. And in any case, why would the Goblin bother to toss her off a bridge if she was already dead in the first place?

So, I decided, that meant she wasn’t dead when she fell. Which meant she died while falling.

But how? How could a simple fall kill her, especially when the art clearly showed that Spidey managed to catch her – by the ankle.

I never asked Gil what he intended to imply by having Spider-Man ‘s web catch Gwen by the leg in just that spot, creating just that arc, torso, and neck and hair arching backward like an upside-down apostrophe. In all probability, Gil was simply trying to execute an elegant layout. But what he drew bad implications from a physics point of view, and even more importantly, from a dramatic and emotional viewpoint.

Spider-Man was haunted by guilt for failing to act, and by the knowledge that his failure to act cost someone he loved his life. Now, looking at Gil’s art, I decided to show that sometimes, even a hero who takes action can fail the one he loves.

Sometimes trying to do good is as futile as doing nothing at all. Sometimes, bad things just happen.

Snap.

After this intro, we get to issue #121, which opens with Peter, Gwen, and Mary Jane Watson visiting a sick and deplorable Harry in bed, after his collapsing in issue #119 and Gwen telling him over the phone (while he was in Canada) in issue #120. Norman Osborn- already angry about his financial instability, blames them for Harry’s drug abuse and subsequential state -, ousts them. A mental breakdown follows and he remembers everything about his life as the Green Goblin. The madness takes over and he vows to kill Spider-Man for all the alleged misery on him and his family.

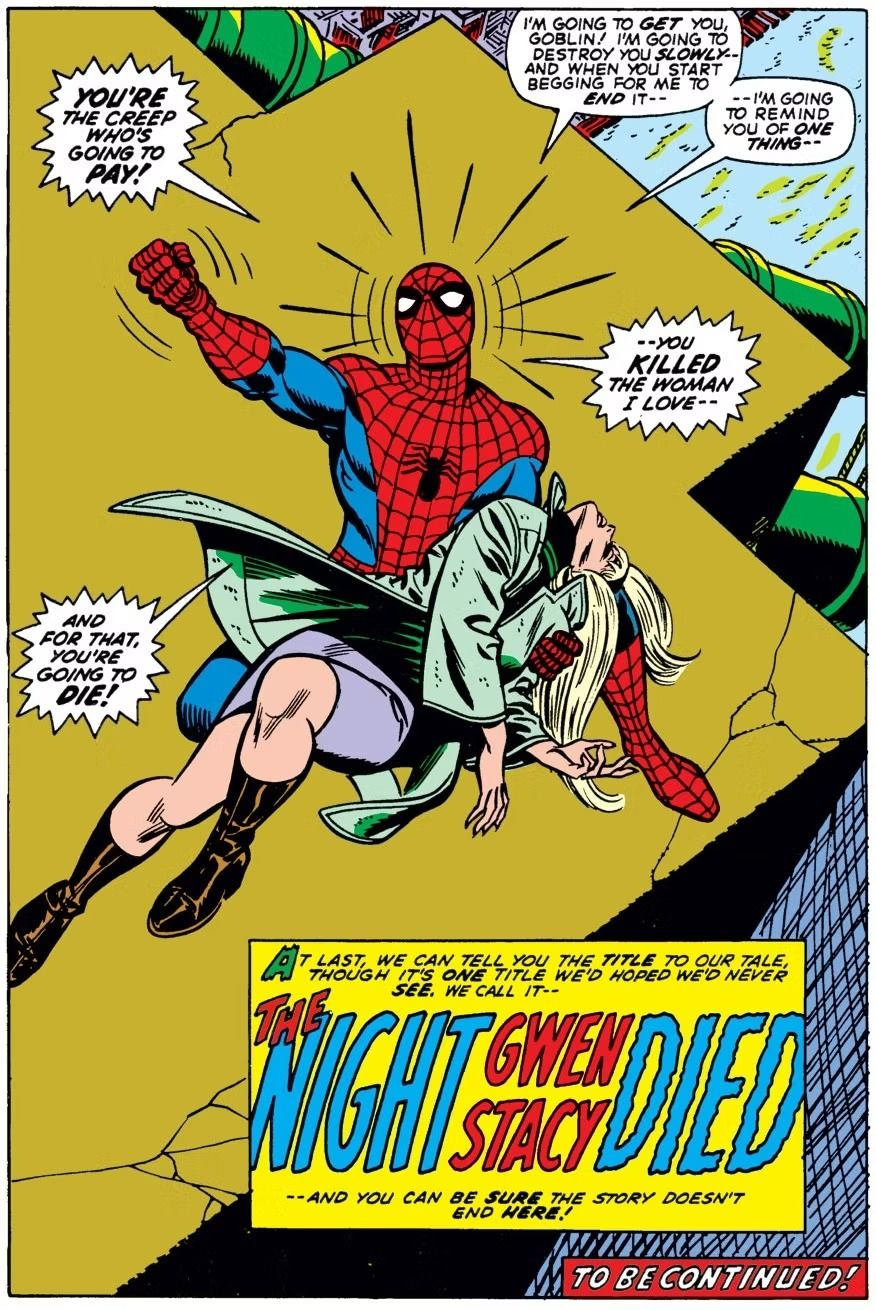

The method? Unmitigated evil: He abducts Gwen and lures Spider-Man to the Brooklyn Bridge. In the climax of a brutal fight, the Green Goblin hits Gwen’s unconscious body with his glider at full force, throwing her out off the top of the bridge – in a dramatic move, Spider-Man shoots a web strand at her, reaching her legs. The whiplash happens. As he pulls her up, he thinks he has saved her. However, it heavily dawns on him she is already dead. Blame becomes his oxygen. The Green Goblin escapes, and Peter cries over Gwen’s corpse and swears revenge.

The rest is history: one of the most iconic pages in superhero comics. The moment things in the comic industry shifted forever, and Spider-Man was right in the eye of the storm that followed.

All Conway wanted was to tell a good tale – but he accomplished much more. That single page alone has reached legendary status in the history of superhero comic books. For Spider-fans in particular, it has become the most shocking and strident moment in the history of The Amazing Spider-Man series.

One cycle of Spider-Man’s life is over.

The following issue (#122) delivered justice and rightful retribution. The usual wisecracking template of the hero is gone; Peter Parker carries an expression of rage, inviting the reader to feel to put himself in his shoes, thanks to Gil Kane’s flawless art. Just imagine the kids or young adults at that time, used to the unlucky, and yet quirky superhero, now having to face his dark side. Besides having that thought to ponder, they’d also have a second hard pill to swallow: this monthly comic showcased (again) the fact that death is also an inescapable fact of life; it suspends the disbelief that this is mere comic book entertainment. Peter’s overbearing guilt, besides justifiable, only adds more weight to it, just like when he captured the burglar who killed the man in his life closest to a father figure.

The story follows. Peter tracks Norman at his home, who is no longer there, but finds a more delusional and sick Harry; unwilling to help him, he asks for Robbie Robertson’s help (in uniform) to successfully track Norman down at a warehouse. Round two ensues and fueled by rage, Spider-Man nearly beats him to death, if not for a moment of moral clarity – he won’t kill. That very moment cost Norman his life due to a failed attempt to regain the upper hand using his damaged glider – the same glider that pushed Gwen off of the bridge impales the Goblin against the wall.

This makes the comeuppance – Spider-Man beating the hell out of Green Goblin, followed by his accidental death – a bittersweet one: it doesn’t change anything, but only reinforces the fault and remorse that the first true Love of his life died because he is Spider-Man; just like his Uncle did. For those actions and reactions, Spider-Man proves once more to be more verisimilar than most superheroes.

In the end, for those who thought then that Peter’s love life was done for, the issue prophesizes its future: Mary Jane Watson. Her decision to stay after being harshly judged by Peter as a carefree party girl speaks volumes. One is gone, and the other stays. From here onwards their relationship would only evolve because they would grow up separate or together.

This last page, though discreet, is equally iconic in terms of character development, using Ditko’s nine-panel grid to emphasize the iconic moment:

In the issues that followed, Gwen appeared a few times: as a clone, in flashbacks, or even as a spiritual harbinger of guilt. For dramatic purposes, it worked so much that, the element of her death itself became part of a guideline on how to make Peter feel miserable and guilty; a reminder of his greatest defeat. On the other hand, as a resolve to depict the nature of his heart and how much he is the kind of man whose Love for a single woman – Mary Jane – enables him to push his limits and stay on track with reason, whenever life as a superhero pushes the limit of his sanity.

Kraven’s Last Hunt is just one of many testaments to as how this element works on his character – and it happened right after their wedding. The man literally crawls out of his grave propelled by one single thought on his mind: MJ.

Years later, Marvel Comics is under a new direction in the 21st century. After introducing bold new aspects into the life of Spider-Man, it’s not difficult to imagine J. Michael Straczynski looking back at the character’s history as a professional writer, and examining the weight of the death of Gwen Stacy in Peter’s life. It’s nonetheless an intriguing study.

SINS PAST – ASM #509 – 514 (vol. 1 – Sep. 2004 – Fev. 2005):

(Cover & Art by Mike Deodato Jr.)

Mary Jane has always wanted to be in the spotlight; she’s a born actress. Right at the beginning of the tale, she’s auditioning for a play called Cats Always Lie. As many already know, performing either on stage or in front of a camera is pretending to be someone else – lying (and so keeping secrets). Through ‘DeNiro’s’ stage director, JMS delivers one critical lesson in acting: “Stop acting… Take the stage, face the lights… And tell the truth.” A foreboding promise for what is yet to come.

Mary Jane lands the part after delivering a straightforward and honest performance. At home and in celebration spirits, Peter confesses to the reader she’s his everything. But then, a letter addressed to Peter comes in the mail, and everything changes: the letter is from Gwen Stacy. Everyone is shocked. As he reads the one-page letter, she (Gwen) says she has done something terrible – related to the time she was in Europe -, and she can’t explain what or how for fear he might leave her forever, but she’s about to and is also very sorry for it. In a conversation with MJ, they go through the timeline of events, from ASM #119-120 to the night she died. They find it strange why the letter has only one page and why the date on the post stamp is recent and not from years ago.

Unable to sleep, he goes to the cemetery to talk to Gwen about it, but he’s not alone; he had assumed someone was messing with him. So when he’s attacked by one masked man and woman. Still, even in the rain, with a trenchcoat, without web-shooters, they only manage to cut him once. A truck passes by and he flees on it.

The next day, he goes through the letter again and is sure that it is connected to the attack. MJ then suggests that paper leaves marks, in case one writes sequential pages on top of the previous; that gives him an idea. Then, an envelope to Peter arrives, containing pictures of May and MJ accompanied by two strangers – whose faces are blurred or blackened. A note is attached to it: “We can kill them whenever we want”.

He goes to Inspector Lamont (Robert Redford alike) for help in examining the letter. The written side is attached to a steel plate to keep it from being read, leaving the blank side to be examined for latent handwriting. It’s a test of trust for both sides. Lamont complies and sends the letter to the lab, keeping his word. After checking on MJ, who’s at the stage rehearsal, he calls Aunt May at Aunt Anna’s, but the call is intercepted by the same man who’s been playing with him. To make matters worse, he throws a gambit: he tells Peter she’s been kidnapped and gives him an address where she is. All he finds in a warehouse is a dummy with a bomb attached to it. He barely makes out of it alive, because the explosion hits him hard. The masked couple shows up and the man consumed by rage beats him over and over; Peter says he doesn’t even know who he is, and that angers him even more. Then finally, names are given: Sarah and Gabriel.

Before they leave Gabriel utters promises of destruction and death. Peter passes out. Enter flashback: Gwen, MJ, and Peter at the Osborn mansion, talking about Harry and Norman’s refusal to take him to a hospital. Gwen wants to leave, as MJ says he needs to get her purse. At the front door, Gwen asks Peter if he loves her and needs reassurance from him no matter what happens. He wakes up, still not understanding a thing.

He goes back to Lamont for the results, and the news isn’t good: though the letter is not complete, some words carry the weight of the world: in her own words, Gwen was pregnant with two babies who were born prematurely – named Gabriel and Sarah.

Atop a building in a state of absolute sorrow, Peter ponders heavily on the possibilities and concludes that those two strong adults would have been children, but not normal ones. Back home, Peter tries to show he’s ok, and though MJ knows it’s for her own protection, her captions state otherwise and reveal more – a convenient piece of the current puzzle: “I have to respect his secrets. Because that’s what I do. I keep people’s secrets.” This is far from over.

He goes back to the cemetery and stands in front of Gwen’s tomb. Unrelently obsessed with the desire to learn the truth, he uses a metal lance to pierce through dirt, her coffin, and the body to get a sample of her DNA. A strong moment. Imagine his guilt and the thought that he might desecrate her body. Gabriel is there, watching from a distance, talking to Sarah. Peter takes the little he can get from the genetic material and invades a genetic lab, given the urgency. He crosses the material collected from the letter with the sample from her coffin. Meanwhile, MJ finds the letter. While waiting for the results, Sarah tracks and finds him there stating the imminence that Gabriel might show up at any minute; holding Spider-Man at gunpoint she confesses that Gabriel wants to prolong Peter’s psychological and emotional torture. Then the computer alarm goes off, informing the results are ready. Faster than her eyes can catch him, Peter disarms and renders Sarah; he removes her mask. She’s the spitting image of her mother, Gwen – head tiara included. The outer window explodes. Sarah moves fast and escapes. Peter checks the results, still flabbergasted by what he just saw in Sarah. The test matches. Gwen wrote the letter. From a distant rooftop, Gabriel says that he’s their father and deserted her. They leave again, and Peter is more dumbfounded.

Back home, MJ confesses to him that he knows about Gwen’s children; and though Peter tries to explain that they had never got that close together, MJ lands the final blow: with a stern and calm expression, she tells Peter she knows who the real father of Gwen’s children is. The pieces start to come together.

Issue #512 – the fourth part of the storyline opens with the opposite side of the camera placement in the conversation, as Peter’s soul is about to be dragged from his body. Mary Jane repeats her statement: she knows. Peter just asks her if she had just found out, or if she knew it all along. And the sad part is… The latter. She knew it all along.

She said Gwen made her swear never to tell – begged her out of desperation. And right here is where the juxtaposition of retrocontinuity happens with plot elements from ASM #121: As MJ and Gwen are watching over Harry, they hear Norman arrive; both agree that Harry must be taken to a Hospital, but as shown in #121, Norman fears for the worse because of his company – more than his son’s. Gwen tells MJ she’ll talk to him about it. The conversation seems to be taking more time than expected. She then leaves Harry’s bedroom to eavesdrop from a near-closed door of Norman’s office; she sees him and Gwen arguing about Harry’s state and how imperative is to take him to a hospital. Norman doesn’t back down and reiterates how he’s weak and ineffective as an Osborn son. Gwen throws the gauntlet: if he’s not taken to a hospital, she’ll keep the children she had with him and raise them with Peter; Osborn doubles it down. Gwen asks him why they were born prematurely – in seven months. An insane Norman just tells her that is due to the Osborn blood – his legacy. As Gwen walks out of his office, she sees a shocked MJ who is listening to their conversation.

Then Peter understands why Osborn went after Gwen and deduces from the events that followed in his life up until that moment that Osborn was the chain that linked them all. How he raised Sarah and Gabriel into believing that Peter was their father and killed her. How he went through her letters and gave them just a page from it to “prove” that.

NOTE: Chronologically, Norman came out of the shadows in the Revelations storyline, which showed the demise of Ben Reilly and the disappearance of Peter and Mj’s newborn baby – a hasty end to an already convoluted and infamous Clone Saga. The retrocontinuity effect went so far back that it made Osborn the one who helped Miles Warren create the first clone of Gwen Stacy. All the details are shown in the Spider-Man: The Osborn Journal (written by Glenn Greenberg and drawn by Kyle Hotz, published on Feb. 97), published right after Revelations.

Notwithstanding, the fact that Gwen laid in bed first with Norman and not him… The secrecy of it, the thought of her choice, the consequence of the act, how Norman seduced and made her feel sorry for him, how he charmed her with his power and magnetism… That’s the ultimate revenge – struck right in the heart. And Peter feels it.

The truth sometimes is a hard pill to swallow. Illustrated here with sheer emotion by Mike Deodato Jr.:

Though brief, it’s an immense outburst of rage. MJ calms him down and rightfully so, expects Peter to hate her. But he doesn’t. He’s a grown man married to this woman who is part of his life. Never has he loved someone more. With a clear mind and all the factors lined up properly, Peter comes to the conclusion that Gwen’s kids are growing and aging abnormally; eventually, they will die. And since he can’t let go of the fact that they represent the last link to her existence, he takes the responsibility to help them, despite the lies ingrained in their hearts.

The next step is to warn them of what is coming. He goes on live TV for a press conference, telling Sarah and Gabriel to meet them where he saw their mother for the last time. But he’s followed by reporters who, from a distance can get an image of them on the bridge, where Gwen was killed; and worse: they broadcast the confrontation live. Soon the police are on-site.

Peter tries to appeal to common sense, by simply laying the truth to the siblings, reiterating how fast they’re aging and how they got superabilities. He also says they were misguided by Norman Osborn – their true father and a maniacal assassin who killed their mother right there and then. Sarah believes him because she knows that he and Gwen never had sex; because he didn’t test his DNA, but only her mother’s. Gabriel, so blinded by rage and refusing to believe in those words, just attacks Spider-Man who tries his hardest to avoid the fight because he wants to save him too. The police start firing; Gabriel suspects a trap and pulls off his gun to shoot Spider-man, who dodges it easily due to his speed. With one fast kick, Gabriel is thrown out of the bridge. But his shot hits Sarah who was in the line of fire. She falls. It’s deja vu all over. But this time he manages to reach her body mid-air and still spins a web to save them from the water impact. He hurries to a hospital. Gabriel survives. Instinctively, the only place left to go is to the one hideout that Osborn made them memorize, should they accomplish the mission of killing Peter. He does find it – the problem is, the hideout has two Goblin suits prepared for them. An inconvenient and shocking truth for Gabriel, whose voice activates a pre-recorded video from Norman himself explaining everything, thus making Peter’s assumptions true.

At the hospital, Spider-Man waits for good news. MJ arrives there shortly thanks to the news broadcast of the scuffle on the bridge. Though the doctor manages the remove the bullet without further damage, there’s the blood loss – and Sarah’s body refuses to accept and matchable type due to the Goblin formula in her system. Then Peter decides to offer his blood for a transfusion. Another piece of retro continuity is inserted:

At the same time, a dazed and confused Gabriel keeps watching the pre-recorded video from Norman, who is already aware of their accelerated aging condition, had created a second-stage serum that would stop the de-aging effect and even increase their strength, with terrible side effects, such as paranoia, psychosis, memory loss, and more. A better-than-death solution? That’s what it means to be an Osborn – to live with such ‘eccentricities’. Gabriel has a choice. He decides to take the serum.

Back at the hospital, the intense blood transfusion makes Peter groggy and weak. MJ poses as a Spider-Groupie to remain by his side in an isolated area. But the fuzz from reporters and police at the hospital leads now a Goblin-clad Gabriel directly to them. The new (and insane) Gray Goblin takes him from the hospital bed for a new fight; on the rooftop, still struggling to stand, Peter is saved by Sarah, armed with a stolen gun from an officer in the building. Fully recovered, she tells Gabriel again the truth: he didn’t Kill Gwen. Osborn is their father. He doesn’t accept it and fires missiles at them from the glider; Sarah shoots back at it. The glider explodes and the short-lived Gray Goblin plunges into the water by the harbor. Too exhausted to even speak, Peter remembers some of the last conversations with Gwen; Sarah leaves. Mary Jane holds him in his arms as he did once a lifeless Gwen for the last time.

From an unknown beach, Gabriel is found by a family passing by; he doesn’t remember who he is or how he got there. Another fine side-effect of the Goblin formula.

And so ends the controversial Sins Past – like a Robert Zemeckis movie, open to speculation and filled with possibilities that will remain unknown only to Straczynski, Axel Alonso, and Joe Quesada. The ultimate retrocontinuity tale in Spider-Man’s chronology, the one that extrapolated the death of Gwen Stacy and became one of the most scorned and reviled Spidey storylines of all time. Justifiably so? Then what are the motives for it?

- Because it demystifies the character of Gwen Stacy;

- Because it is badly written;

- Both.

It is worth mentioning that Spider-Man fans rank amongst the most faithful and passionate in superhero comics; hence its backlash. And that must be taken into consideration. Sins Past caused such a louder and angrier disturbance in the community, that put the Clone Saga retaliation into shame. No reader saw that coming.

A particular irony is that both storylines push Norman Osborn (once again) into the podium as not only the nemesis of Spider-Man but Peter Parker as well. A bold move from (Marvel) editorial was showing his rise as the main villain in the Marvel Universe. And whenever he made a move towards it, evilness and madness followed. Look no further than Warren Ellis’ run on Thunderbolts (#110 – #121, Vol. 1) and Brian Michael Bendis’ Dark Avengers (#1 – #16, Vol. 1) – both drawn by Mike Deodato Jr. Both series deliver astounding insights into his mind (and soul), besides his natural talent to lie and corrupt – not far behind from the Joker, Magneto, Luthor, or the Red Skull. Issue #11 (with extra art by Greg Horn) is Bendis’ nod to Straczynski’s work on ASM.

One of the rationale superhero comic book fans keep coming back to the same fantasy tales every month is the fulfillment of seeing them overcoming adversities and defeating evil. And when it strikes them personally, we as readers take some of the impact. The Death of Gwen Stacy is the indirect ‘how-to manual’ to write villains attacking superheroes personally. The death of Elektra, Jason Todd, Karen Page, Kyle Rayner’s girlfriend, Identity Crisis, and more have Gerry Conway to thank for it.

So, for the purpose of offering a counterpoint to the only aforementioned options, don’t villains always return? And don’t they act more viciously than the last time? Isn’t that what they do? Isn’t that what comic book superhero writers are supposed to do – to come up with new ways to defeat their archenemies?

After developing so many new aspects of Spider-Man’s origin of his powers, J. Michael Straczynski had the opportunity to tackle the character’s history. Why not start with his greatest defeat – as many writers before him have – the one that left him a psychological scar? From a writer’s perspective, such emotional damage is a rich territory worth exploring. No other superhero character had a learning curve like that: how naive Peter was to keep living under the illusion that he could get away with having a chaotic Superhero life and still keep it secret from his girlfriend.

If Peter Parker is the most relatable character by verisimilitude, why not his supporting cast as well, starting with Gwen? Like anyone else at a young age, she can also be impressionable by someone with strength, power, and maturity – traits that her boyfriend seriously lacked; he was too busy saving the day and everyone they knew in common kept branding him as a coward, and not there for her when she needed him. And more: she’s an orphan without siblings who desperately needed solace. So it makes sense; who could ever give her emotional support under so much stress and loneliness? It makes sense she was seduced by all of those elements. By adding psychological and emotional layers to her character profile, her actions are understandable.

JMS complements it:

He has always been portrayed as a charismatic, strong-willed guy. But look, can we get real here for a moment? Anybody out there who hasn’t known at least one young woman who — in or out of a relationship with somebody else — hasn’t made a mistake and slept with an older, possibly charismatic guy…raise your hand. (…) We handled the aging thing by indicating that the solution Norman used to become the Goblin, which gave him an accelerated healing factor, also affected his DNA, and in turn his children’s DNA, in ways consistent with accelerated biology.” Are you telling me that there aren’t women who wouldn’t fall for that? (…) And I will say that some of the criticism is, itself, in my opinion, out of line in terms of the rage directed not against me but against Gwen.

Osborn didn’t force her – she willingly surrendered herself to him.

It’s common knowledge that women are attracted to older men with money, knowledge, experience, and power. Why wouldn’t Gwen? Don’t people make mistakes, or act on impulse? This is not the desecration of Gwen Stacy – quite the opposite: back then, Gerry Conway looked at the nature of her character and understood that, in the long haul, she would eventually hinder Peter’s guilty crusade against evil even more. Was she special? Yes. Did she have depth? No – to the point that he introduced MJ to stay at the very end of the story; it’s like he knew it all along that she was designed to be the real love of Peter’s life; a door had been closed, but he was not alone. She stood inside with him. That’s why JMS went full-bore into the lore. This is a story about Mary Jane, Gwen, and Norman Osborn’s sins. Sins of violence and silence, and how Peter is the one still paying for them.

It’s a tale about keeping secrets and the lengths people go to keep them like that. It’s not by accident that it starts with one character on a theater stage, learning how to be honest in lying. That’s Mary Jane, who had always done her best to pretend she was pretending to be someone else. The stage is set to present a drama about “real people” – their secrets, lies, and pacts. Aren’t real people imperfect? And doesn’t the last issue of Amazing Fantasy show exactly that? A kid so lonely, scared, and angry that, once imbued with power became so selfish that one single decision cost him everything? Why couldn’t we look at Gwen with the same metric? Has she become so sanctified that whatever else is done to her is considered a sacrilege? Couldn’t she fail or be wrong?

This is also a tale about the true legacy of evil. and how characters can go to great lengths of time to protect their deep dark secrets because those very secrets are embedded/embellished in sins – sins against those they Love. It is part of human nature; people in their families and friends circles do it all the time. And by that assertion, we’re proven that once again, those we love the most are the ones who disappoint and hurt us harder. A constant in Peter and MJ’s relationship from the last page of ASM#122 to this storyline and beyond. Sins Past is a story about one of the most difficult moments they had to endure in their marriage.

On that, JMS pushes the assertion further:

We all make mistakes…that’s part of what’s at the core of Sins Past. The question is how we deal with our mistakes — as Gwen dealt honorably and strongly with hers — and how others deal with our mistakes — as Peter never stops caring for Gwen even though he knows what happened. Isn’t that a good message to send to people? That we can own up to our mistakes and take responsibility and try to make things better? That those we love can see our mistakes and still care for us afterward?

By looking back at all the plot elements and characters coming together it’s difficult to ignore from a writer’s perspective that these two panels in issue #120 provide a nice “future flashback” to the chronicle:

It’s not difficult to imagine that behind those tears, Gwen might be crying over something else besides Harry’s health, if looked through the new storyline perspective.

The application of new elements to this chapter of Peter Parker’s life does not change anything about her; it just introduces new layers into the Gwen Stacy character. Structure-wise, it doesn’t fail to deliver. It is a well-written narrative. But for some fans, such new elements break decades of perception of what Gwen used to be; it became unacceptable. And the same goes for Mary Jane: “How could she?” So to some eyes (and hearts) both women failed Peter, thus betraying the trust of the reader as well.

Another factor to be taken under consideration is Marvel’s direction of characters and storylines during Joe Quesada‘s reign as E-i-C: many elements were either retconned or revealed with the unveiling of secrets, identities, and the return of characters. It happened to Matt Murdock and his secret identity ousted, Logan (aka James Howlett) and his son(!), Steve Rogers and the return of Bucky, Frank Castle’s last tour on Vietnam that defined him as the Punisher and his daughter (!), the Illuminati, the Original Sin event; whereas in Spider-Man’s macrocosm J. Jonah Jameson‘s teenage years (in a Tangled Web issue), Aunt May finds out Peter’s secret life as a hero and have the best conversation in superhero comics, Gwen Stacy’s secret (here), and Peter himself who took the hardest hit during the superhero Civil War by revealing his secret identity to the world (but that’s a topic for another post). What was old became new again and retrocontinuity was part of the order of business, just like DC has done many times over.

It is a fact in superhero comics – sometimes, writers revisit the past to tell a story from a different perspective. It’s not only what the story is, but how it is told.

But it could have been worse: Straczynski’s original concept for the storyline was for Gabriel and Sarah to be Peter’s children. But Joe Q rejected the idea; especially regarding what he had in mind for the future.

Still, if that was a story about Norman damaging Peter’s life in the past, one can only wonder how a story of him battling the Green Goblin would be, had Straczynski remained in the title.

(One minor detail: on issue #509, the Amazing Spider-Man logo changes – again.

The final word on this tale is left to Straczynski himself, in an interview for the website Fanboy Planet, conducted by Derek McCraw,

JMS: The problem, of course, is that you will always hear more from those who don’t like something than from those who do. That’s as cold certain a fact as you can ever find, and any person with a background in public opinion measurement will tell you that. So I really don’t put a lot of stock in it, and I think your assumption isn’t supported by the numbers. Three people shouting in a room of thirty makes for a loud room… But again you have to separate volume from numbers.

(…)

Storytelling means you have to take chances. Look over at the competitors…what was done with Jason Todd, or Hal Jordan over the years, or others there and at Marvel…if you don’t shake things up once in a while, the book stagnates. Yeah, you could do a book just for the core fans, for people who don’t want to see any changes at all…but you’d be selling maybe fifteen thousand books a month, and it would go out of print instantly. If you don’t take chances and try things, you’re just telling the same story over and over…yeah, the costumes change, but it’s all just fights.

(…)

Some folks want a character who doesn’t change, about whom we can never learn anything new, no surprises…someone frozen in amber for all time in a state of perfection. For thirty years. Nothing new about a character in three decades. The dust is an inch thick at that point.

(…)

The theme, for me, in Spidey is the need for people to talk to each other, and that we can accept more than those who love us think we can accept.

When Peter came out of the metaphorical closet, he discovered that Aunt May could handle his secret without dying. It became a metaphor for a lot of people who are afraid to tell their loved ones the secrets we all think they can’t handle. The situation with Gwen is much the same. The one person we think could not be able to handle this — not the fans, not the editors, not the writer, but Peter — is able to handle this information and accept that it happened, and deal with what follows. Peter’s character, as written, never says about Gwen what some of the fans who claim to be her fans say about her. He does not call her a whore, or a tramp, or a slut. He loves her…and takes on the responsibility of trying to save her kids because they are a piece of her, the ONLY surviving pieces of her.

If you find a better definition of a hero, let me know.

In conclusion, if Sins Past still remains as the utter demystification and destruction of Gwendolyne Stacy, don’t worry. Here’s the perfect alternative:

Hey, Aqu@ – thanks so much!

Good to see you back!

I’m quite busy right now, so I don’t know when I get to read the whole piece, but I’m looking forward to it!