With Becoming Superman, J. Michael Strazysnki became the first Amazing Spider-Man writer with his own memoir. The book, which covers his horrific upbringing as well as stories of the entertainment industry, has gotten notices in places like NPR, the BBC, and the Washington Post. And it’s a bestseller. Considering the emphasis of the Crawlspace, I’m going to consider three main facets. First and foremost, is his book good? But for our interests, what does he say about his work on Spider-Man? And how does his background inform his take on Spider-Man?

An issue with the book is that aspects of it are so radically different that some readers will enjoy different sections significantly more than others. Someone interested in learning about how a kid who grows up in poverty realizes the power of storytelling might not care as much about Straczysnki’s arguments with cable TV producers. Someone looking for Hollywood gossip from a guy who wrote a Clint Eastwood directed Angelina Jolie film and was a showrunner on the Wachowskis Netflix show might not want to read about why comics were so meaningful to him when he was a kid. Someone looking for a better understanding of science fiction might not be prepared for the section about how his grandmother molested him (his upbringing was truly terrible). This stuff, and the rest (his experiences with Image and Marvel, his exposure to a church that started going culty) is really good, as the different strands are all written well. It’s a messy life and he’s not focusing on just one aspect.

One thing that becomes clear is that the superhero that meant the most to him is Superman, who he was exposed to thanks to George Reeves’ The Adventures of Superman, and the Max Fleischer cartoons. It gave him a role model that was missing in his real life.

No, Superman was never going to be my father, but if I worked at it really hard, maybe one day I could become Superman. The idea didn’t seem improbable given an Adventures of Superman episode about a guy who found Superman’s impenetrable costume; putting it on made him nearly as invulnerable as Superman.

While he cared more about Superman, he did like Spider-Man just fine, recalling his experiences reading comics at his aunt’s house.

With her help, I acquired a healthy collection, including the first appearances of Spider-Man in Amazing Fantasy #15 and Thor in Journey Into Mystery #83 and a full run, starting from issue one, of The Fantastic Four, The X-Men, The Incredible Hulk, as well as Silver Age titles from DC: Superman, The Flash, Blackhawk, Atom, Green Lantern, Aquaman, and Metal Men. But Superman remained my chief focus, and his depiction by Curt Swan became the true, iconic image against which all later versions will be measured.

An early lesson he gained from the superheroes was to endure against bullies, a theme that has popped up in his Spider-Man work.

From that day on, whenever they came after me, I would ball up to ward off my blows, the Superman of America badge inside my jacket pressed against my chest, eyes closed, waiting for my chance to mouth off. I pretended that I didn’t feel the blows, that I was invulnerable, that I was Superman. And I learned just how much I could take.

This ended up helping him survive a vicious gang-beating when he was in his twenties.

One of his early mentors was the radio drama pioneer Norman Corwin. As a student, he broke into a college office in order to register for two of Corwin’s writing classes. He was caught but Corwin liked his writing sample so much he took him on as an assistant.

When he got into writing it wasn’t in prestigious places. He had been helped by industries preferring outsiders and new perspectives, so minor work as a journalist led to opportunities in Childrens’ animation since his background appeared exotic in that environment. An early job on the mostly forgotten series Jayce and the Wheeled Warriors showed his high standards even working in disreputable fields.

Coming from a love of worldbuilding, Larry (Ditillo) and I were incapable of writing scripts where things just happen just because they happen. There has to be some kind of rationale. So we fought incessantly against the series’ various dumbnesses, making life hell for Haskell and Jim, who just wanted to get this over with so they could move onto something more rewarding. Why were we hammering them with questions about physics in a show about giant interstellar plants with a fetish for all-wheel drives, for chissakes? What the hell was wrong with us?

He would try large scale stories in television, starting with the animated series Captain Power, where he seeded a season-long arc. It was important for him to have larger stories that developed over time, and things occurring with a specific rationale. The latter to be the source of his main disagreement with Joe Quesada about the end of One More Day.

The book tells his experiences in mostly chronological order, even in the case of a story he worked on for decades, the screenplay about Christine Collins, a single mother who was declared insane after her son went missing, and she refused to accept another child in his place. He considered why he felt the story was so important.

The answer, I realized, lay in Christine’s refusal to lay down to those in power. The LAPD, the chief of police, and the doctors who helped commit her to an asylum for the crime of disagreeing with the police, hit her as hard as they could, trying to break her will. In her struggle I saw echoes of my own past, getting pounded by bullies or Elders determined to make me recant what I knew to be true. She was a fighter and her efforts deserved to be recognized.

He had a view on Batman and Robin that influenced his take on the Ghostbusters cartoon, where he argued for the removal of kid sidekicks.

Most kids don’t want to be Robin, they want to be Batman, because if they work really hard, there’s a chance they might someday become Batman. But Robin is their own age and can already do things that are impossible for them.

He came to comics because he had burned his bridges in television, and hadn’t yet cracked the script for the Christine Collins film. He started with Rising Stars, meant to go against the norm. Where most bestsellers “were single-character books that starred a costumed superhero marred by tragic flaws” this would be an ensemble. Where most comic characters never grow old “Peter Parker is always in his twenties, Superman somewhere in his thirties” this would cover generations. The success of that led to Midnight Nation, covering themes that he had been interested in for for some time about how there appear to be two different worlds: the shiny facade and the dark reality, a lesson that Peter Parker would discover as well.

His first Marvel offer was Amazing Spider-Man. His early concerns were whether it was too ambitious to start at Marvel with an open-ended run on a flagship title, rather than a mini-series, but he saw value in exploring that story.

While Superman has always been my icon, as a kid I collected every issue of The Amazing Spider-Man that I could find, including his debut in Amazing Fantasy #15 (all later destroyed by my father.) I was drawn to Spider-Man because like me, Peter Parker was skinny, geeky and often bullied by other kids. For him to get amazing powers was every kid’s wish come true.

He continued going against the grain, where his run cut the supporting cast to focus on May & MJ, and where he eschewed the classic rogues gallery primarily for new villains or for shorter stories dealing with contemporary topics (gun violence, teen homelesseness, etc.) And we could see themes that are important to him in his run such as the value of doing the right thing even when it costs you everything—explored in the first Morlun story and Civil War—how everyone is capable of deciding their future for good or ill—explored in “Skin Deep” with Peter’s former classmate—and the importance of honesty over secrets.

From Becoming Superman, we get a sense of what he considers important about his run years later. He probably didn’t see most of his Spider-Man stories as meaningful as adapting an old Rod Serling outline for an episode of the 1980s Twilight Zone, but here’s much he’s proud of. He cared about May.

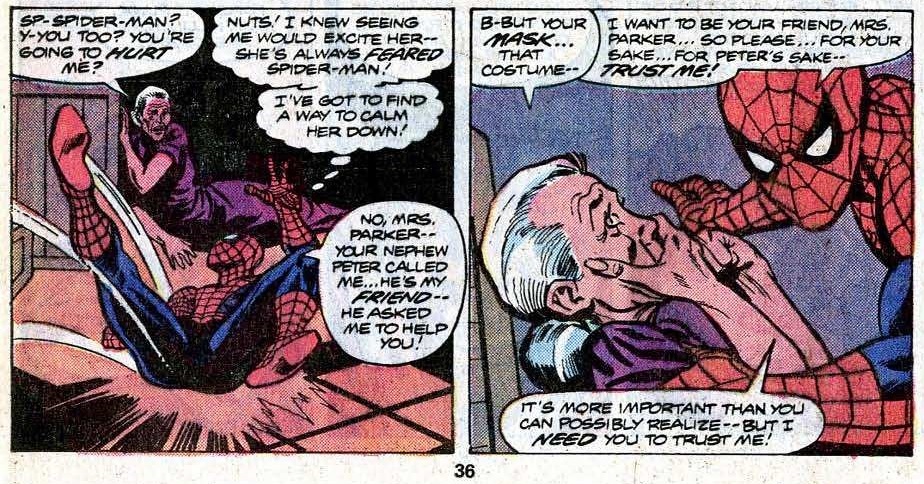

I used those early issues to repair Peter’s broken relationship with Mary Jane, and to do something that I’d wanted to see for decades. Peter’s aunt May had always been portrayed as a fragile, frail old woman who would fall over dead if she learned his secret, but I never bought that sexist perspective for a second. This was a woman who buried Peter’s parents and her own husband, then raised a young boy alone. That takes courage, stamina and a spine of solid titanium. Peter may have gotten his powers form the spider but he got his strength from Aunt May, so during my run she finally discovers his secret. Not only does she not die, she embraces this side of his life and becomes his greatest ally. I wanted to show that those who love us can carry the burdens of our secrets and accept the truth of who we really are.

He was proud of the longevity of the run, and spent a few few pages discussing the September 11 issue, where he put his own thoughts into Spider-Man in response to this tragedy. When considering the story, he was stuck on the idea that there are no words to handle the tragedy, but then followed that thought as a writer.

Around this time, he struggled with the TV show Jeremiah in ways he can’t fully describe due to potential lawsuits, and started seeing a therapist, developing key insights into his life around the time.

Gradually, the terms Asperger’s syndrome, reactive attachment disorder, and PTSD entered the conversation. They explained my social awkwardness and all-absorbing interest in subjects like wirting comics, and, yes, Superman; also, my compulsive self-reliance, lack of emotional resonance, inability to form lasting relationships and a preference for being alone.

The end of his Spider-Man run coincided with one of the toughest times in his life. Comics didn’t pay enough to cover his costs (a house in LA, support for an ex-wife) and he wasn’t getting any work in television. I suppose it’s a bit of a relief that he doesn’t write about One More Day all that much. Given his willingness to describe disputes with George RR Martin when they were both on the 1980s Twilight Zone, all the secrets he reveals about family and former colleagues, as well as his general refusal to compromise, it seems to be something that didn’t affect him all that much (although it could also be that he had the commercial sense not to go into a convoluted digression on a retcon-heavy comics plot point.)

He finally cracks the script for Changeling, and that leads to a new period of creative success. The boy who was inspired by Superman gets to reimagine the man of steel for DC’s Earth One line of graphic novels, which brings everything full circle.

At the end, we get a sense of a man who refuses to compromise and tries at times to subvert the system, as he recalls in a section on Babylon 5.

These character arcs would have to be crafted in secret and rolled out carefully because while I’d told Warners that we were doing a five-year arc (which they still didn’t believe was feasible) they assumed the characters would end the show roughly where they began. Had they known what i had in mind they would never have approved it. This left a very narrow runway for storytelling; if the audience figured out too early where this was going, the element of surprise would be gone. If Warner Bros. figured it out too soon, I would be gone.

In a lot of memoirs, the writers recall the arguments in which they’re right with the subtext that everyone should have listened to them, and this is no departure from the norm. With some of these stories, there are potentially different sides to the arguments that he doesn’t present. For instance, some Warner executives would probably prefer that showrunners be honest about long-term goals. It is a little suspicious that the stories that are meaningful to him tend to be hits and/ or the things that would generate commercial interest. He talks about decades spent working on what ends up being the Eastwood/ Jolie film, rather than long-running projects that flopped. It remains a worthwhile read, and the Hollywood challenges are entertaining.

We do see the biographical influences that could have affected his Spider-Man work. His father was as monstrous as the Norman Osborn of Sins Past. While he wrote a comic book in which Aunt May told Peter that people who love one another have to be honest with themselves, he was a few years away from realizing that his marriage wasn’t good for himself or his wife. He had a view of Peter Parker as more predator than prey that matched his own realization as a struggling young writer that emotion, specifically rage, was the missing ingredient in his early stories. He may have loved Superman, but he did get four stories on the Crawlspace list of the top 50 Spider-Man stories.

Anyone else read the book? What did you guys think?

It’s a good text.

Thanks for sharing it, Thomas!

I wasn’t a huge fan of his run when it originally came out. He dismissed established continuity and his dialogue was overwrought and his arcs relied too much on mystical and supernatural threats instead of street-level enemies. He also had some duds, ‘Sins Past’ being the obvious worst, but there were a couple other mediocre stories as well.

In recently reappraising his run and knowing his flaws going into it, I did appreciate it more, especially the early JRJr collaboration (I’m still lukewarm on his later Deodato collaboration). He did great character work with Aunt May and some stories were true classics like ‘Coming Home’ (the Morlun arc), the Carlyle vs Doc Ock in LA story, and ‘Doomed Affairs’ (with Peter and MJ meeting at the airport while Doc Doom is there) and even the Digger arc was fun.

My original grade for his run would be a C+ at the time, but if I were doing a retrospective now I’d give it a B+.

Back in the month of September I had a chance to get the book your talking about here at my local Barnes and Noble store. I should have used my in store cupon to purchase it, but I looked through it and liked what I did see in the book … I was looking for his reasons for OMD. I think I will look at your link in the article for best results.