Given today’s date I felt we should talk about…Mary Jane…and drugs…

Well…not exactly.

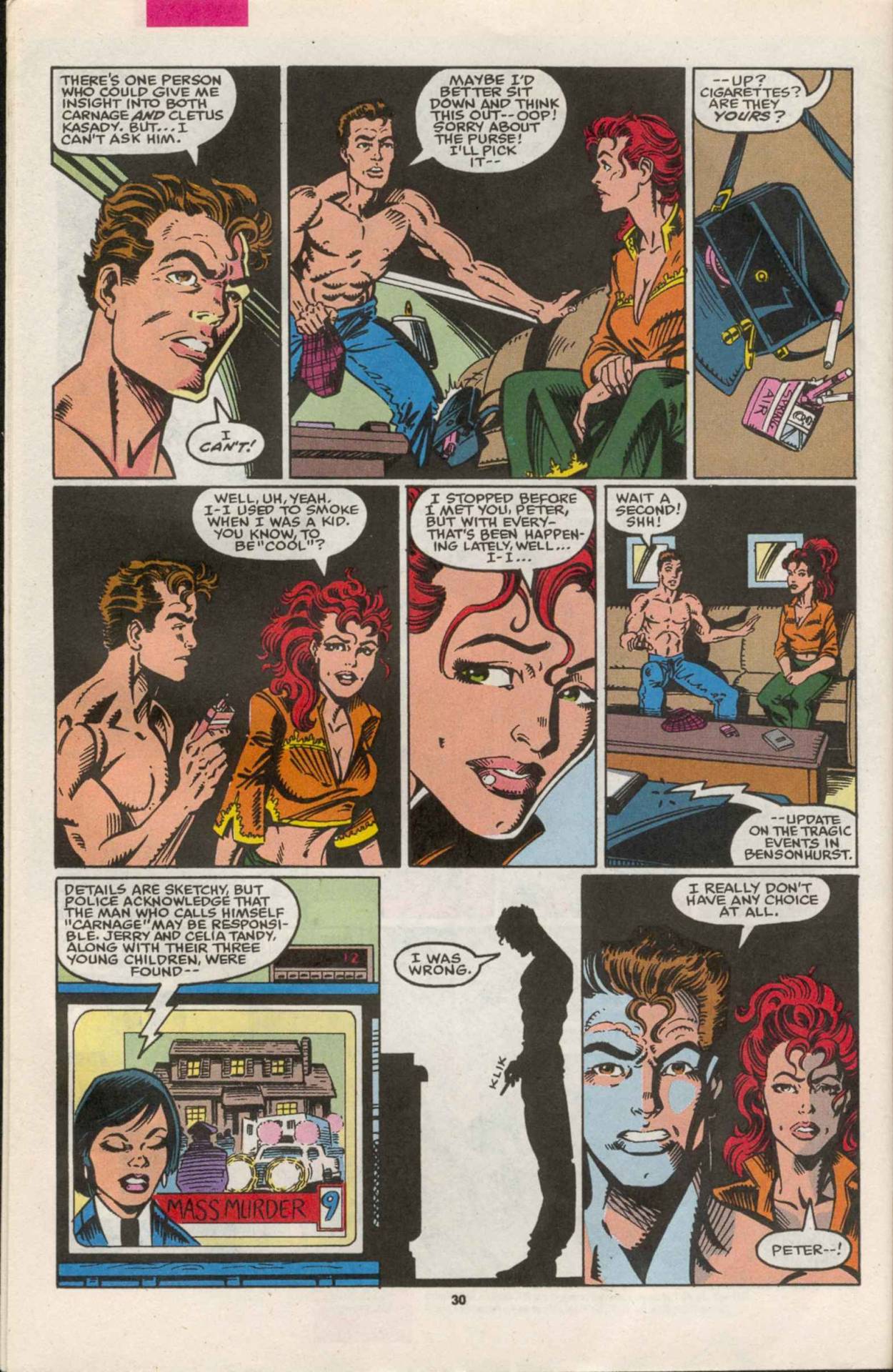

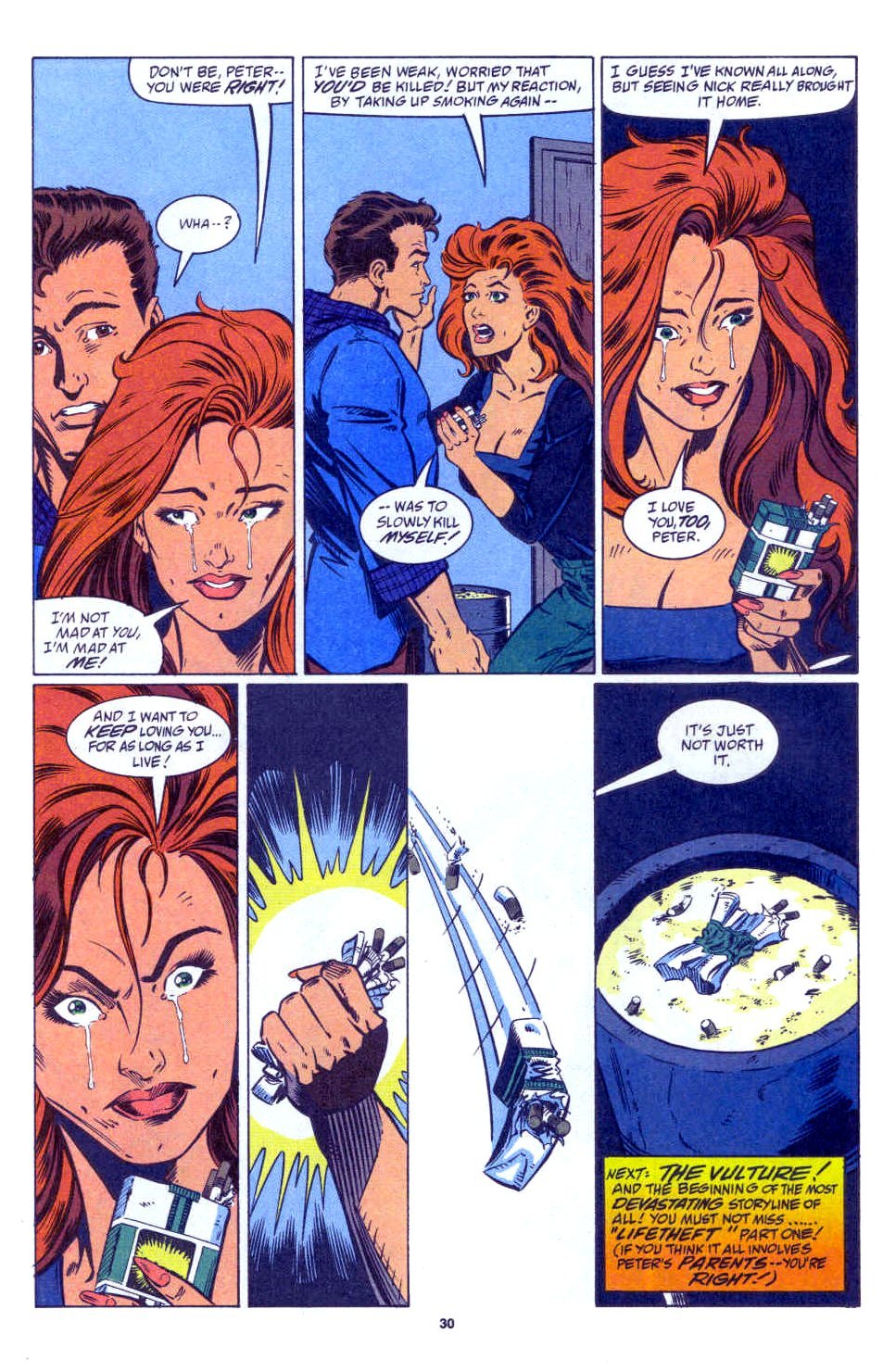

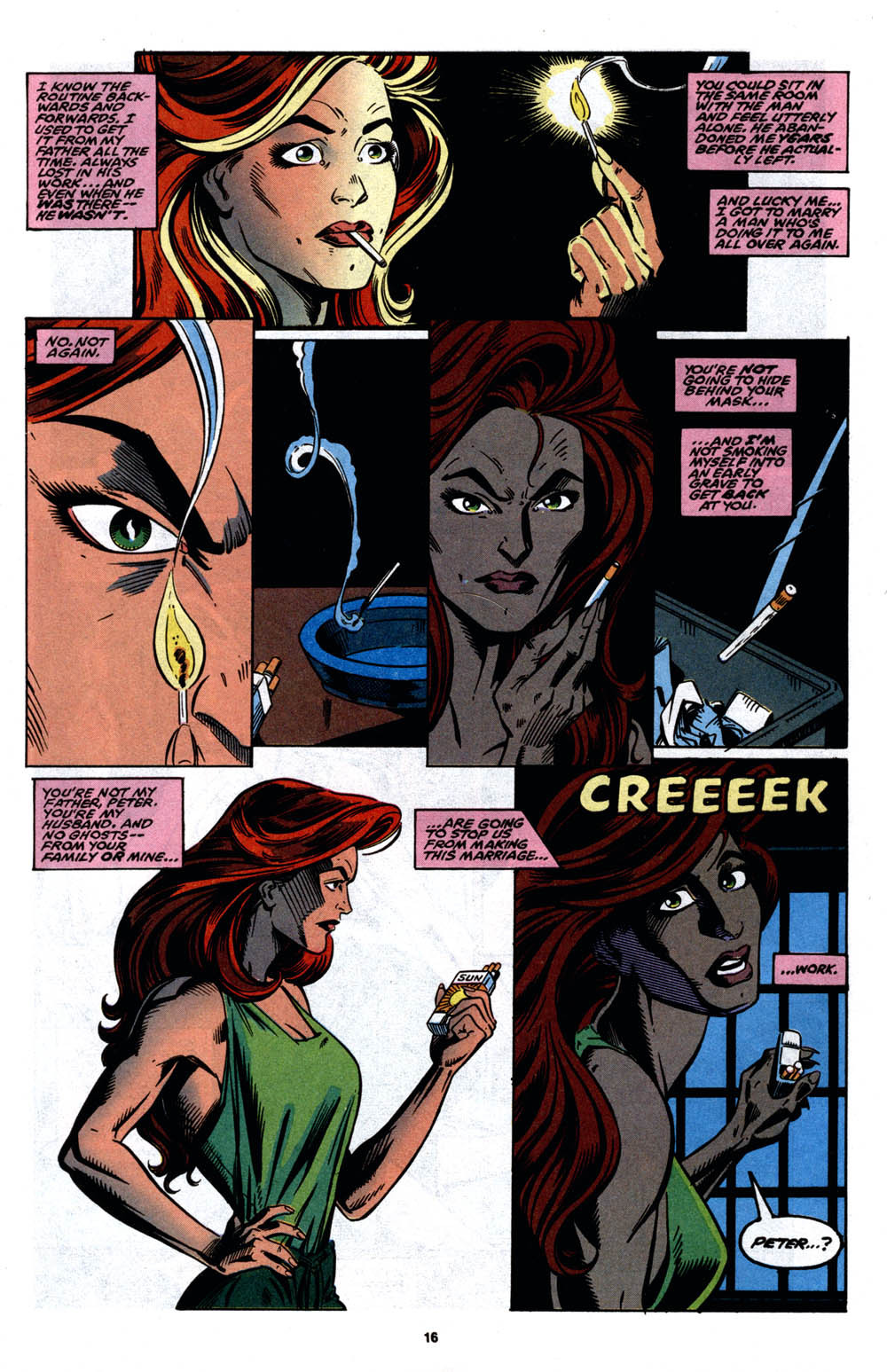

Rather I wanted to use today to discuss a controversial topic regarding MJ’s character. That of her smoking addiction in the 1990s chiefly under writer David Michelinie’s run on ASM.

Don’t worry this isn’t going to be an exhaustive dissection of every scene touching upon subplot. It’s more about the weird reaction the fanbase has had to it over the years.

Any time I’ve seen the topic discussed it’s talked about in negative terms. Unfortunately it’s been lost to time now but I distinctly recall former Spider-Man writer Dan Slott referencing the smoking subplot as part of why the marriage was bad. Crawlspace’s very own J.R. ‘Madgoblin’ Fettinger has even referred to the subplot as a ‘clumsy’ attempt to generate conflict within Peter and MJ’s relationship?

By and large the feeling seems to be that the smoking subplot was ‘just bad’. But the rationale for why it is deemed bad seems to amount to…because it was about smoking. And when I say it is regarded as bad what I really mean is I’ve routinely encountered people react with bile and venom (no pun intended) over the subplot.

Essentially the subplot is regarded as bad because doing a subplot about smoking addiction is just an inherently bad storyline to do period, almost like it’s trying to be a preachy PSA over something that isn’t a big deal.

I however very much disagree with probably everyone on this topic. To be blunt the attitude most commentators seem to adopt towards Mary Jane’s smoking subplot seems to be incredibly lacking in perspective, exaggerating what is wrong with the storyline and its mere existence.

A lot of this I feel ties into fan biases against Michelinie’s run, the 1990s, the marriage or Mary Jane’s character in general which serve to judge all those things unfairly.* However I’m not going to discuss those today, but instead talk about why the animosity towards the subplot is just plain illogical.

Longevity

To begin with the subplot’s longevity and impact are grossly out of proportion with how many parts of fandom view it in the context of Michelinie’s run, the 1990s or indeed the marriage years for the character.

The subplot was introduced in ASM #361, the true debut of Carnage.

It was essentially resolved in ASM #385.

Though very occasionally brought up after that point Mary Jane never smoked again and to date no conflict between her or Peter ever arose again due to it.

To all intents and purposes this was a subplot that played out across a mere two years worth of issues. And it wasn’t even brought up or heavily focussed upon in every single one of those issues. Like I said, fans exaggerated the scope and impact of the subplot. It wasn’t even the only subplot involving MJ’s character during that time period.

How serious is smoking?

The second perspective issue fandom has with the subplot is the seeming trivialization of the issue. It seems to treat the mere fact that there was ever a subplot about MJ being addicted to smoking as over the top, clumsy and just all round illegitimate as a story concept because smoking addiction isn’t a serious enough story to warrant that kind of attention.

The thing is though…that it is.

I do not myself want to be accused of preaching here or overstating the obvious but the truth is…it’s not like smoking isn’t a bad thing…like a really, really bad thing.

There is a lot to say about it but a lot is summarized in this document.

In a nutshell smoking is the single biggest leading cause of preventable deaths.

If you were to combine everyone who died annually from alcohol, meth, heroin, cocaine and ecstasy smoking on its own would kill more than double that number. Also bear in mind that for every individual who dies due to smoking around thirty people suffer from smoking related illnesses.

Hell to quote Chris Rock from his Never Scared stand-up performance:

Cigarettes are so ****ing dangerous it kills mother****ers that don’t smoke, okay?

Although less people in the USA are smoking now than essentially any point in their history a massive chunk of the population still does it. In the early 1990s the percentage in America was close to 25% of the entire adult population alone. That wasn’t counting non-adult smokers or second hand smokers.

So the topic categorically isn’t something to be trivialized and is a million miles away from being invalid grounds to make a story about when comic books, movies and TV shows routinely do stories about alcoholism and drug abuse which are actually comparatively less harmful to the overall population.**

Nature of Spider-Man

But there is an even more glaring perspective problem fandom has when it comes to the subplot and to properly contextualize this I am going to quote ‘the late’ Donovan Morgan Grant. Specifically I am going to quote part of his review of the ‘Rocket Racer’ episode of the 1994 Spider-Man the Animated Series.

The gist of the episode is about the hardships of a young black person who is falsely accused of being a thief. It is one of the single most reviled episodes of the show, to an extent because of its animation, the use of D-list characters Rocket Racer and Big Wheel but most of all due to the subject matter it focuses upon.

Though touching on a starkly different subject than Mary Jane’s smoking addiction Donovan eloquently summed up the inherent illogic of lambasting that sort of subject matter in the context of Spider-Man’s narrative.

Please understand that I am not saying that the Spider-Man stories should mostly be about various social issues or that the escapism present in the stories isn’t very important.

What I mean is that it’s thoroughly disingenuous for certain fans to hold any Spider-Man story in contempt for utilizing real life issues or on occasion focusing upon them given the inherent nature of the character and his series since…well actually since page 1 of Amazing Fantasy #15.

You could even make the argument that Spider-Man in his earliest days was itself commenting upon the state of medical welfare in America due to how desperate Peter struggled to afford proper medical care for Aunt May.

One of the most iconic Spider-Man stories of all time was the Death of Jean DeWolff which was in a sense touching upon mid 1980s concerns with violent street crime and the limits of ‘law and order’ approaches to it, a subject continued to be addressed by the author of that story (Peter David) in consequent issues.

Another iconic Spider-Man story colloquially referred to as ‘The Drug Trilogy’ directly and brilliantly touched upon the issue of drug addiction using the character of Harry Osborn. And that was back in 1971!

ASM #68-71 in 1969 no less discussed the Civil Rights Movement with Joe Robertson and his son Randy even disagreeing over the right course of action to improve the lives of African Americans

Various stories during the 1960s and especially 1970s even touched upon the Vietnam War, with Flash Thompson being subtlety written to have what today we’d call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

In fact just a few years after the smoking subplot was resolved there was a subplot focussed upon Flash Thompson’s newly developed alcoholism which to this day few people have ever criticised.

Flash again was used to touch upon social issues during (some of the few good stories of) Brand New Day when he became disabled. Later when he became Agent Venom his disability and alcoholism was touched upon again as the Venom symbiote (which could create temporary legs for him) became a metaphor for addiction. Though I have my own reservations about Agent Venom conceptually, early on when that subject matter was very much central to the series the book was positively received.

So Spider-Man has a long history of off and on touching upon social issues and fans have at worst tended to be okay with it.

All of which makes the animosity to the smoking subplot rather disingenuous.

Why are these sorts of stories and subjects permissible within the world of Spider-Man but Mary Jane coping with the entirely realistic stresses of being married to a superhero by falling upon a health damaging crutch that causes organic conflict to arise between her and her family not okay?

Cliché?

Well some might respond that the answer is because it was ‘cliché’? The problem with such a response though is that…it wasn’t.

Few stories in wider media (outside of PSA’s which aren’t even actual stories intended for entertainment) honestly approached the subject in that way. At most it tended to be a throwaway line or visual of someone stressed out smoking. It was rarely a subplot focussed upon in the way it was in Spidey’s comics.

And moreover even if it had been done a lot in wider media it hadn’t been done particularly frequently (if at all) in mainstream American comic books, and certainly not superhero comic books.

If we are going to declare a comic book as cliché for utilizing any given trope prevalent in any and all media we are going to have to write off classics countless classic tales and runs.

The Master Planner Trilogy, The Death of Gwen Stacy, the Death of Jean DeWolff, at least half of Frank Miller’s Daredevil run, 90% of classic Thor stories (in particular everything between him and Loki), Batman: Year One, the first arc of George Perez’s Wonder Woman run, the Dark Phoenix Saga, Demon in a Bottle, Jim Steranko’s Nick Fury work and virtually every Avengers story you can think of.

ALL of those contain elements, many of which are centrepieces of the stories/runs, that had been done innumerable times in other mass media that the public would have been all too aware of.

At least half of the events of the Death of Jean DeWolff storyline owe a spiritual debt to Dirty Harry and Charles Bronson movies. Heck Wolverine’s entire character in the 1980s owes a massive debt to most of Clint Eastwood’s work up until that point.

And that is not even diving into how ‘cliché’ those stories become when we compare to wider media from other countries who also indulge in such tropes, possibly even more so over a longer period of time. On this basis the iconic scene from the Master Planner Trilogy becomes even less special or impressive when compared to the myriad of content from Japan.

Broadly speaking only in truly exceptional circumstances should a comic book story be judged as cliché based upon it touching upon similar topics or story tropes found in wider non-comic book media.

Conclusion

In conclusion if you do not personally enjoy the smoking subplot from the 1990s more power to you. Our preferences are just what they are, no getting around them.

And by all means lets discuss our views upon the execution of the subplot, how it worked, how it might’ve failed, how it might have been improved.

But please can we all just stop pretending like the story was somehow inherently wrong for mere existing and worthy of bile.

*Note that when I say ‘unfairly’ I do not mean all those things are faultless; far from it. I mean segments of fandom don’t give those things a fair trial when they assess or critique them. In other words something may genuinely be bad but how bad is exaggerated and any positive qualities ignored or spun as negatives.

I’ve unfortunately encountered this routinely with people commenting upon the Clone Saga which consists of in excess of 100 comic books by various creative teams. And yet the Saga is broad brushed as wall-to-wall irredeemable garbage when realistically that’d just be extremely unlikely, is not true and is an inappropriate way to evaluate what is ultimately an era of Spider-Man not a singular storyline.

**It is especially disingenuous when one considers stories about drug abuse, drug dealers (from both sides of the law) are so commonplace and oversaturated that nobody needs to make another story about them ever again. For myself growing up in the 1990s and 2000s I was simply bored of stories about drugs and drug addiction because there were so many that they were cliché. I outright enjoyed stories about alcoholism because they were at least a little different.