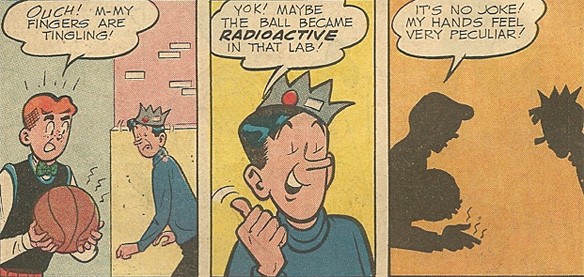

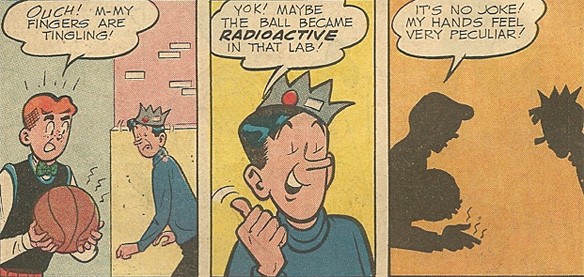

In the last entry, I wrote about two conflicting views on Spider-Man: whether the appeal of the character is that he has grown, or whether it is that he is young. This ties to another argument about whether one prefers the illusion of change to a commitment to change. A complicating factor in discussions is that there is also a third possibility: a series where there is practically no change, which some people think is the same thing as the illusion of change. This may be why one of the complaints against recent Spider-Man comics was that Peter Parker was turned into Archie Andrews, a character incapable of any change or growth. Every now and then, some peopledo express a preference for this idea, and have advocated for Marvel to go further in this direction with their characters, truly adopting the old-fashioned Archie approach, asking for entirely self-contained storylines with no significant arc-to-arc continuity at all.

Let’s consider what it would mean to have no change. In this format, Peter Parker would not benefit from a status quo conducive to longer term stories, and there would be very few major developments to the status quo. In the rare event that there are any major changes, these would happen over the course of a single adventure, a bit like a TV show where there are sometimes changes during the occasional season premiere/ finale. At one point, this approach was the norm for comic books and television. It predates either medium. Sherlock Holmes writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle took credit for combining the addictive appeal of a serial with the accessibility of a short story in this manner. He explained in his autobiography Memories and Adventures, an excerpt of which appeared in the Wordsworth Classics edition of The Best Sherlock Holmes Short Stories:

It had struck me that a single character running through a series, if it only engaged the reader, would bind that reader to that particular magazine. On the other hand, it seemed to me that the ordinary serial might be an impediment rather than a help to a magazine, since sooner or later, one missed one number and soon lost all interest. Clearly, the ideal compromise was a character which carried through, yet installments were complete unto themselves, so that the purchaser was always sure he could relish the whole contents of the magazine. I believe I was the first to realize this and The Strand Magazine was the first to put it into practice.

As a note, when describing comic books, I’ll sometimes use the term issue to issue continuity. It’s not entirely literal, as that would exclude multi-part stories, which may be the preference for some readers who want every story to be done-in-one, but is not a requirement for this type of approach. Obviously, Part 2 would pick from Part 1. A TPB-length storyline would literally have issue to issue continuity, but it could end without anything occurring that would be referenced in the next TPB. There isn’t much practical difference between a four part story where everything resets at the end, and a single issue story where the same thing happens. Examples of these kinds of stories would be the typical arcs from Batman anthology titles like Legends of the Dark Knight, along with many licensed comics for film and television properties, which tend to leave the protagonist at the same place at the end of the story as he was at the beginning. This has typically not been the case with most Spider-Man stories.

It makes the books more accessible if the status quo of one issue is exactly the same as it was a few months earlier. A new reader doesn’t have to expend any energy wondering about how things have changed, while a returning reader can jump right back in if the status quo is exactly the same as when he left the book. Late artists and writers will be less of a problem, as Marvel could just put in fill‑in work in their stead, and no one would care as neither project will have had any change to the status quo, preventing any confusion regarding the intended order. Reprints are also more appealing if there’s no difference between these and the new material. Coordination between multiple titles becomes significantly easier if there’s nothing in Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man to affect the state of the hero in Amazing Spider-Man.

There are also some significant disadvantages to this approach. In his book Everything Bad is Good For You, author Stephen Johnson noted that stories in television and movies have become more intricate, relying on the audience understanding prior developments. Compare Arrested Development and Community to the Honeymooners, or the Lord of the Rings series to the Sean Connery James Bond films in terms of narrative complexity. This has also become true of comics, and the storytelling would seem infantile to anyone who has seen Breaking Bad or Game of Thrones if the writers couldn’t reference prior continuity or relationships, or feature several ongoing (and sometimes) intersecting narratives.

Marvel titles are available on their Digital Comics Unlimited program six months after release, so a series where there’s no change to the status quo would encourage readers to just wait a few months for any new stories. There’s more of a need for getting readers interested in new issues than ever before, so strategies that worked before the advent of the back issue market might not make sense now.

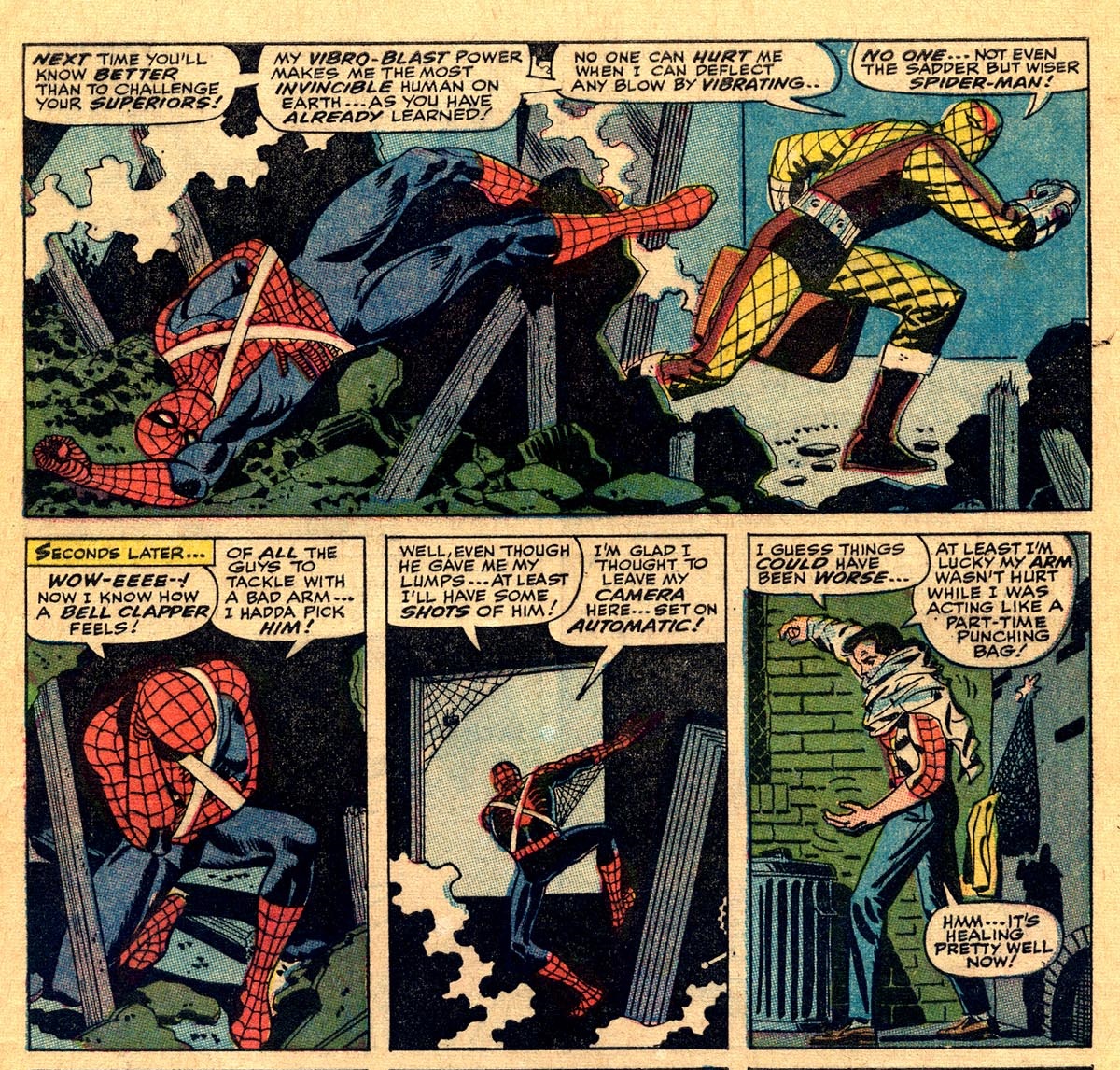

Stories also seem more significant if there’s the chance of major ramifications later. Readers won’t be worried over any private subplot if there’s no possibility that Peter Parker will suffer a bit. The chance that a landlord will evict Peter Parker is more of a concern if the reader knows that the next issue can begin with a homeless Peter looking for a place to stay. A battle between Spider-Man and the Vulture is more interesting if there’s the possibility that Peter’s going to be dealing with the injuries several issues later, or in a guest-appearance on another title.

A lack of clear issue to issue continuity was one of the flaws of the Brand New Day era of Amazing Spider-Man, when there were times when ten issues could have been released out of sequence with very little impact. This was generally fixed rather than ignored, so that the major stories still mattered, and smaller stories had ripples several issues later.

Other series like Batman and Superman have featured standalone adventures for big chunks of their existence, although the comparison is imperfect. Peter Parker’s adventures (and subplots) were far more important to the appeal of the Spider-Man book than Clark Kent’s private life was to the appeal of Superman. Pre-Crisis Superman often had no long-term subplots, so it didn’t really matter what order issues came out in. You can’t really say that about the Silver Age Peter Parker, starting with Amazing Spider-Man #9 or so. Elements of his private life in one issue (Gwen Stacy thinking he assaulted her elderly father, Betty Brant getting jealous of Liz Allen) could cause trouble for him for months to come.

The Superman comics had a different structure, in that Clark Kent didn’t change at all from issue to issue. Independent of the Superman plot, he almost always ended the story at the same place he began it, no matter how outlandish the developments in the story may be (Clark Kent’s father returns from the dead! Superman goes to an alternate dimension in which Krypton was never destroyed!) That’s very different from Peter Parker, for whom stuff can change during the course of a story (he can be fired/ hired, have a falling out with his aunt that lasts for an entire year’s worth of comics, get dumped, meet a girl, etc.) Going back to the Lee/ Ditko run, even minor events had consequences as when the principal calls Peter to his office to discuss a fight with Flash Thompson two issues earlier. A key part of the series’s appeal was to see what happens next to Peter Parker, and what the consequences for the actions would be. Peter Parker quit graduate school in Amazing Spider-Man #243. He didn’t break the news to Aunt May until Amazing Spider-Man #253. She was still upset at him about it in Amazing Spider-Man #271, and their relationship was fairly rocky for some time. To give another example, Gwen Stacy thinks she sees Peter Parker assault her elderly father in Amazing Spider-Man #60, causing a rift between the two. Her father remembers that Peter meant well in Amazing Spider-Man #64. She’s able to find Peter and reconcile in Amazing Spider-Man #66. During this time, Spider-Man fights the Kingpin, Medusa, the Vulture, a bunch of prisoners and Mysterio. Readers were sure that Spidey would survive these battles. They weren’t so sure about his relationship with a girl.

The traditional Sherlock Holmes form of storytelling was also done with Batman. Though he can have a smaller consistent supporting staff, he’s uniquely suited for frequent cases involving new one-off characters, as Bruce Wayne has a lot of minor business associates and many potential romantic interests, along with the resources to travel anywhere in the world the Batman may be needed. This allows for much variety, even if he inevitably returns to Gotham City, where he’ll once again interact with people who have no idea about his earlier adventures in exotic locations, and no reason to discuss it with him.

Even if there were an actual Spider-Archie approach, things can change. Recurring characters can die, hook-up or change jobs. New characters can be introduced. But these are rare, which does make every new development more special. There may also be a lot of change in a short amount of time, to kick off a new editorial direction, as with the first two issues of Julie Schwartz’s silver age Batman run, as the costume changed, Alfred was seemingly killed off, and Aunt Harriet moved in.

There can also be moments that are significant for readers. Family Guy writer Gary Jenetti described the most recent episode as one that isn’t essential to understanding future episodes, but still features an important revelation about a character. As he said, “We get to learn more about (Stewie) in this episode. It deepens our understanding of him going further, but I don’t foresee it’s something that will be acknowledged again — nor do I think it should.” To be fair, this can be done just as easily in a series with a different storytelling model, including a Commitment to Change. In the Spider-Man comics, examples might be Peter’s visit with the kid who collects Spider-Man, the Paul Jenkins Peter Parker recalling encounters with Uncle Ben, or Ultimate Aunt May revealing her secret fears in a therapy session.

The standalone model has fallen out of favor so extensively that it can’t even be used to describe Archie or the typical licensed books. Marvel’s Star Wars books have crossovers and long-running plotlines, as does Mark Waid’s relaunched Archie. It is also worth noting that there have been plenty of changes in Batman, and Superman, especially in recent years. Batman and Catwoman got engaged, part of a larger story that writer Tom King had been seeding for some time. That followed runs by Grant Morrison and Scott Snyder, which had years-long mega-arcs, as well as major changes to the mythos.

There are still a lot of things you can’t do without any arc to arc changes. Long-term plotting is severely limited. New perspectives of earlier tales (the basis for a lot of great twists) would be discouraged, as that involves referencing stories that new readers might not be familiar with. Character arcs typically require change across several storylines, so that can’t really be done with this format, which probably goes against a chief attraction of the Spider-Man books as longer narratives build to a boiling point.

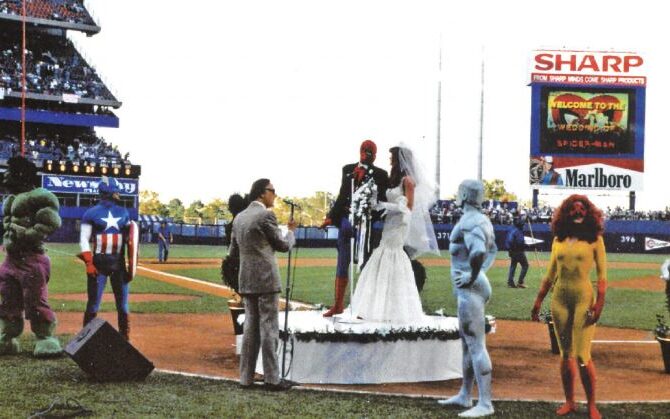

The illusion of change is one of the major alternatives to having no change at all. I think it works in the specific context of the Spider-Man comics, and a few other long-running series. It doesn’t mean Game of Thrones should be made under that model, as that’s a series meant to have a complete beginning, middle and end, where the idea that major characters can and will die is very much part of the brand. TV has reached a level where it can also tell those kinds of stories: where viewers can keep track of dozens of characters with ongoing intersecting storylines, and subtle references to events from earlier years. Certain economic realities have incentivized bringing things in a close, lest actors get to expensive.

I’ll note that modern storytelling has grown more complex to the point where other media are able to imitate the complexity of lengthy novels, and there’s room for argument that we may be in a media environment which doesn’t allow for a series that is stuck in the middle. Technology has reached a stage where we can access easily all the previous adventures. There is also the possibility that society has changed enough since the 60s that it might not make sense to pretend the relatively young lead of a series set in a contemporary world was the same guy who was a teenager in comic books published in the 1960s.

The problem with moving towards the end of the story is that once you go in that direction, there is no going back. The Spider-Man books have been around for a long time, and part of the reason is careful management to make sure the character doesn’t change from what he was in the beginning.

That wasn’t always the case. The Lee/ Ditko run occurred at a time when Stan Lee thought superheroes were basically a fad and wasn’t worried about the long-term prospects of the series. So there were some major changes (IE- Peter graduating high school and going to college, Peter breaking up with Betty, Peter and Liz drifting apart) pretty early on.

There were less changes per issue in the next decade. Stuff happened that had major consequences but not at the same rate. Gwen and Peter were together for more issues than Peter spent in high school, prior to her untimely death, in a story that paved the way for Harry Osborn becoming the Green Goblin.

Things changed at around Issue 150. Len Wein had a run where Peter Parker’s status quo ended up the same as it began (college undergrad dating MJ and working as a photographer for the Daily Bugle), but the supporting cast had some developments (Jonah fell in love, Liz and Harry fell in love, Betty and Ned got married, etc.) Marv Wolfman had changes that were cosmetic or illusory (Peter went from college to grad school, Peter broke up with MJ, Aunt May was believed dead, the Burglar-who hadn’t been seen since Amazing Fantasy 15-died.) But the first major irreversible development for Peter in about a decade of comics was Mary Jane revealing that she knew Peter’s secret identity.

The illusion of change is somewhere between the old Archie format of no change at all, and novelistic growth. It still allows for continuity. It’s more the idea that the writer isn’t taking over the character from their predecessor, but borrowing the character from their successor. Things can happen that are meaningful, but it would be because someone wants to tell those stories, rather than that they’re obliged to do so. The Black Cat can be introduced in Wolfman’s run, and it’ll be up to Stern and Mantlo whether they want to keep her around. If you didn’t like Dan Slott’s run or you’re worried about Nick Spencer, it can be a bit of a relief to know that the next person isn’t going to have to reference it, and can just focus on their own stories, or build on the material of writers you like.

With the commitment to change, there is the potential of breaking the character if someone tells a bad story, or a good story that logically reaches the point where the story’s over, and just no longer as interesting. The Spider-Man comics are sometimes compared to other runs where writers took big risks with long-running characters (Alan Moore on Swamp Thing, Frank Miller on Daredevil, Peter David on the Hulk.) However, Spider-Man is bigger than Daredevil, or the Hulk. Miller and PAD were able to tell the stories they did because no one cared as much if they failed. There is also a bias towards remembering the good stuff, and forgetting all the mediocre runs on B-list titles, and the books that didn’t survive major shake-ups. Spider-Man’s story engine was also strong enough to not require big changes in the first place.

What do you guys think? Do you have a preference for a particular approach to the series? And if you do want to see more growth, should CB Celuski, Joe Quesada and Nick Spencer make bold and permanent changes to the Spider-Man comics?

Al, looking forward to your response.

I should note that while I am generally in favor of the Illusion of Change, my points on the hypothetical approach of pretty much no change whatsoever are more about explaining a philosophy to the series than advocating for it. I also did make a few points in favor of a commitment to change approach, which I know you ptefer.

Enigma_2099, I suppose the argument is that disconnected short stories could still be good, though an audience probably won’t be in any rush to read those with all the other available options.

Mark, interesting point on Anakin. A different aspect on that is that the audience for the prequels generally knew what would happen to Anakin, so when he had his downfall it felt inevitable, and it was known that it would end with redemption. His core was that he was the man who would become Darth Vader. There isn’t that flexibility with Spidey, since members of the audience has a clear idea of what the core is.

As a side note, a critic talked about how his kids had a different take on Star Wars because they saw the prequels first: From their first perspective, Anakin was a good guy who hit a rough patch and got it together in the end.

First things first – I was scoffing at the Superman title for saying he welded the sub with x-rays, but then I looked it up and you can actually weld with x-rays, so there’s one to grow on.

As far as the illusion of change vs. actual change, that’s a tough one. Spider-Man’s appeal early on was his progress out of high school and into college. We like that he grows with us, albeit at a slower pace. However, if a character progresses too far away from the core character, we don’t like it.

I think it takes a writer of a caliber higher than is normal to be able to pull that off successfully, and even then, there will still be the chorus of “that’s not the Spidey I know!” I think the key is to progress the character while still keeping the character who they are at the core. A great example of this is the progression of Anakin Skywalker throughout the six movies. Compare the little kid in movie one to the deadly villain in movie 5. He’s still arrogant and struggles between love of family and love of power. Peter Parker as a CEO could work. Being poor is not his core. The problem that many people had with that story is that it didn’t feel like Peter Parker. I know that I consistently gave higher grades to comics where Peter was relatively not in them – not because I don’t like Peter, but that I didn’t recognize the Peter I was reading. That may be a fault of my own and not the writer since there were many people who did enjoy the books.

I don’t know that there will ever be a perfect answer to that problem. I’ll have to agree with Enigma_2099 (which I hate to do because he called Bag-Man stupid) – just tell me good stories. Be it a one shot or an arc – make me glad that I am $4 poorer because I am all the richer for having read an awesome story.

This whole thing was unnecessary. Whether you prefer status quo or shakeup, in the end you just want good stories to justify the FOUR DOLLARS THEY TAKE FROM YOU MONTH AFTER MONTH FOR SERIALIZED FICTION. And who’s gonna pay that for a bunch of disconnected short stories?

I will have to respond to this and the last article int he near future because I heavily disagree with it.

This was an interesting read, but I was disappointed after reading the blurb and Archie screenshot on the front page – I thought this article would be about Archie getting spider-powers.